How Friendsgiving Took Over Millennial Culture

In the past five or so years, hosting a Thanksgiving meal among friends a week before the actual holiday has become a standard part of the celebration for many young adults.

Every year for the past five or so, the Emily Post Institute—long considered the leading authority on matters of manners and courtesy—fields at least one or two etiquette questions about “Friendsgiving.” Usually they come from people in their 20s and 30s, says Lizzie Post, the co-president of the institute and the eponymous etiquette authority’s great-great-granddaughter. The advice seekers are often anxious about exactly how to host a Friendsgiving party, a Thanksgiving-themed meal for their close friends.

When, for example, is a Friendsgiving supposed to take place? (The weekend before Thanksgiving or the weekend prior, usually.) Is it an imposition to ask everyone to gather for a Thanksgiving meal a week or so before they’ll have another? (Not necessarily, but Post recommends deviating a little from the traditional Thanksgiving menu to avoid stealing the real Thanksgiving’s thunder.) And what’s the most polite and egalitarian way to organize a Friendsgiving? (Hands down, potluck-style, with dishes and supplies assigned via a Google spreadsheet. “From everything from organizing parties to lending out camping equipment, shared spreadsheets are amazing,” Post says.)

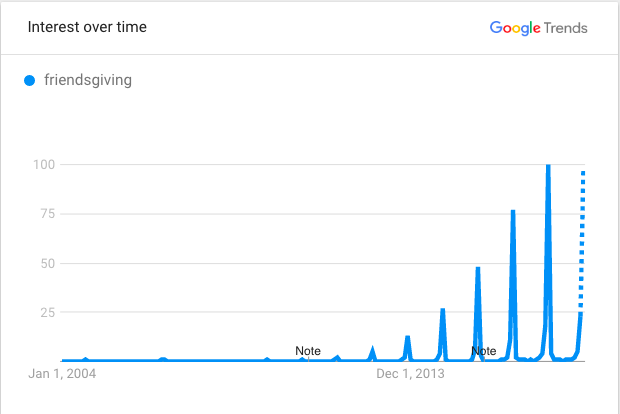

The Google Trends graph of the word Friendsgiving—indicating how often people have Googled the term over the past nearly six years—looks like a row of increasingly menacing icicles flipped upside down: From 2004 to 2012, virtually nobody was scouring the internet for the term, but a tiny nub of search interest in November 2013 gave way to a small spike in November 2014, followed by exponentially intensifying spikes the next three Novembers. Food publications such as Chowhound and Taste of Home have recently released Friendsgiving host guides; almost 960,000 posts pop up when you search Instagram for the hashtag #friendsgiving. At press time, some 3,000 of those had been added in the past 24 hours.

Post and others I spoke to for this story agree that Friendsgiving seems to have evolved in recent years from a sort of ad hoc Thanksgiving replacement (implemented when people found themselves far away from family on the holiday but near friends) to a common in-addition-to-Thanksgiving event, one that’s exclusively for friends. In other words, Friendsgiving has become a widely celebrated American holiday in its own right—and while it’s hard to know in real time what cultural shifts or forces have led to the rise of Friendsgiving, there are a few compelling theories as to why you may be seeing the term pop up again and again in Venmo transactions this week.

It is, of course, distinctly possible that the surging popularity of Friendsgiving is directly tied to the power of portmanteaus. Slapping a catchy name onto an existing concept can, after all, make it seem trendy or suddenly ubiquitous, even if the thing itself has been around for decades (see: bromance or jorts). But one way to understand Friendsgiving’s recent popularity is as the expansion of the Thanksgiving holiday into something more like a Thanksgiving season.

As Matthew Dennis, a University of Oregon professor emeritus who’s studied the nearly 400-year history of Thanksgiving, points out, holiday celebrations are always evolving. For example, “Halloween has really transformed a lot in the last generation or two. It’s completely different from what it used to be,” he says. Ever since the late 1980s or 1990s, “it’s almost as much an adult holiday as it is a kids’ holiday.” Plus, it’s not unheard of for certain holiday celebrations to sprawl into the surrounding days and weeks: Lots of friend groups have Christmas or winter holiday parties in the lead-up to whatever they might have planned with their families on the actual holidays. So do offices—which have also lately become common sites for Friendsgivings.

Natalie Sportelli, a 25-year-old content and brand manager in New York, has participated in weekday work-lunch Friendsgivings at both her current job and her last job. “Q4 is really stressful. Heading into Thanksgiving and then the rush to the end of the year, it’s a really nice stress reliever,” she says. “And it’s like a teaser for the main event.” (To emphasize that the office Friendsgiving is about relieving stress and not adding to it, this year she and her colleagues ordered a turkey for delivery to the office pantry rather than assigning someone the task of roasting one.)

The “friends” part of Friendsgiving, however, is a somewhat novel element added to the Thanksgiving tradition, Dennis says. For almost as long as Thanksgiving has existed, it’s been considered a holiday to spend with family—or, at the very least, its strong ties to family developed long before it became a federal holiday in 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation that made Thanksgiving a national holiday at the urging of the writer and magazine editor Sarah Josepha Hale. But even before then, Dennis says, “people who were spread all over the country were encouraged to come home for Thanksgiving. ‘Home for Thanksgiving’ became a mantra.” Lithographs from around that time, he points out, often depict people traveling home for Thanksgiving. “Given that the United States was a mobile society and people were moving and spreading out everywhere, Thanksgiving was a moment when people wished to reconstitute their families.”

So another reason Thanksgiving celebrations have changed may be that families themselves have changed—and nonrelatives have become more likely to take on family-like roles in people’s lives. Given what we know about the Millennial generation’s habit of delaying marriage and parenthood into later stages of life compared with prior generations, it makes sense to Dennis that, especially for those who remain unmarried and/or childless well into their adult years, the most important people in their lives might be friends.

When childless or unmarried adults consider themselves to be in a temporary, transitional phase, with marriage and kids and traditional adulthood hallmarks such as homeownership just around the corner, they may not place as much emphasis on friends or Friendsgiving, Dennis theorizes. But if they believe they’ll remain childless or unmarried for a long time, “maybe there’s more of a motivation to do this kind of self-constituting of family and community.”

It’s also possible, he notes, that young adults with the space and equipment to host a dinner party might find themselves eager to host a grown-up Thanksgiving meal but not in a position within their own families to host the “official” event.

Malcolm Harris, meanwhile—the author of Kids These Days: Human Capital and the Making of Millennials—sees something darker at work in the “Friendsgiving” phenomenon. Harris thinks affixing the “cutesy” label of Friendsgiving onto a scraped-together, potluck-style event popular with Millennials that will never actually rival the lavish spreads of real Thanksgiving implies approval by the powers that be of Millennial adults’ lower income and lower living standards compared with those of prior generations. “Friendsgiving,” he says, “is a propaganda weapon used by the ruling class to further their plans for wage stagnation.”

But for some, Friendsgiving is a pricey event unto itself. The preholiday holiday has become such a staple of some people’s lives that it’s become—much like family Thanksgiving—an event to travel to from out of town. For example, 26-year-old Roshawna “Ro” Myers of Virginia Beach, Virginia, will drive four hours this weekend to make it to her best friend’s Friendsgiving in Washington, D.C. It’s their friend group’s third year celebrating together, and she’s “already counting down.”

Now that all her friends are adults and have moved to different places for work and school, “we’re not always able to see each other. Even if I see my best friend one weekend, I’m not able to see everyone together,” Myers says. “So Friendsgiving is when everybody’s like, ‘Okay, we’re all gonna be here this weekend to see each other.’ If you miss somebody and you want to see them and catch up, that’s the time.” This year—she checks her group text thread to get the exact head count—14 people will be in attendance.

Danielle Ireland, 39, was an early adopter of the Friendsgiving tradition; her annual gathering started out simply as a helpful “practice run” for her pub-trivia team in Milwaukee to try its Thanksgiving dishes before the big day. But in the “sevenish” years since that inaugural event, it’s become a raucous, boozy (and kid-free) annual reunion—and she’s moved away to Virginia. This year, flights were too expensive for Ireland to attend the event, but she usually makes the trip out to Milwaukee. “This is my ‘framily,’” she says, smushing together friends and family. “The family I picked. I love my biological family, but there is something magical about this group of people.” Plus, the cooking is always an adventure: One guest insists on bringing a “vintage dish” (usually involving a Jell-O mold) every year, and “there is nothing more exciting,” she says, “than watching your friends almost set the house on fire.”

The institution of Friendsgiving may, to some, feel like Thanksgiving overkill. But Dennis, the Oregon professor emeritus, who was unfamiliar with the growing Friendsgiving tradition until I interviewed him for this story, finds a pre-Thanksgiving Friendsgiving to be a perfectly acceptable extension of the holiday. “In some ways, the thing that’s distinctive about Thanksgiving is that it’s not Christmas. It’s not about gift-giving, it’s not about spending a lot of money. A lot of it should be homemade and improvisational. Whereas Christmas is, well, you know, this bonanza of commerce,” he says. Thanksgiving has managed to hang on to its original ideals: hospitality, generosity, inclusion. What’s more inclusive than expanding the holiday to include friends as well as family?

And perhaps if you really think about it, Dennis says, you could conceive of Friendsgiving as a way of bringing Thanksgiving back to its roots. “The first Thanksgiving, in the fall of 1621, was made up of the white English settlers of Plymouth Colony and their native neighbors, who outnumbered them by a lot. The idea was to have a Thanksgiving to create friends,” he says. “It was, aspirationally, a Friendsgiving, in a way.”