What Amazon Does to Poor Cities

The debate over Amazon’s HQ2 obscures the company’s rapid expansion of warehouses in low-income areas.

SAN BERNARDINO, Calif.—This community was still reeling from the recession in 2012 when it got a piece of what seemed like good news. Amazon, the global internet retailer, was opening a massive 950,000-square-foot distribution center, one of its first in California, and hiring more than 1,000 people here.“This opportunity is a rare and wonderful thing,” San Bernardino Mayor Pat Morris told a local newspaper at the time.

In the months and years that followed, Amazon dramatically expanded its footprint in and around San Bernardino, a city 60 miles east of Los Angeles. The company now employs more than 15,000 full-time workers in eight fulfillment centers (where goods are stored and then packed for shipment) and one sortation center (where packages are organized by delivery area) in the Inland Empire, the desert region bordering Los Angeles that encompasses Riverside and San Bernardino counties. This expansion provided a lifeline to the struggling region, creating jobs and contributing tax revenue to an area sorely in need of both. In San Bernardino, the unemployment rate that was as high as 15 percent in 2012 is now 5 percent.

Yet in many ways, Amazon has not been a “rare and wonderful” opportunity for San Bernardino. Workers say the warehouse jobs are grueling and high stress, and that few people are able to stay in them long enough to reap the offered benefits, many of which don’t become available until people have been with the company a year or more. Some of the jobs Amazon creates are seasonal or temporary, thrusting workers into a precarious situation in which they don’t know how many hours they’ll work a week or what their schedule will be. Though the company does pay more than the minimum wage, and offers benefits such as tuition reimbursement, health care, and stock options, the nature of the work obviates many of those benefits, workers say. “It’s a step back from where we were,” says Pat Morris, now the former mayor, about the jobs that Amazon offers. “But it’s a lot better than where we would otherwise be,” he says.

San Bernardino is just one of the many communities across the country grappling with the same question: Is any new job a good job? These places, many located on the outskirts of major cities, have lost retail and manufacturing jobs and, in many cases, are still recovering from the recession and desperate to attract economic activity. This often means battling each other to lure companies like Amazon, which is rapidly expanding its distribution centers across the country. But as the experience of San Bernardino shows, Amazon can exacerbate the economic problems that city leaders had hoped it would solve. The share of people living in poverty in San Bernardino was at 28.1 percent in 2016, the most recent year for which census data is available, compared to 23.4 in 2011, the year before Amazon arrived. The median household income in 2016, at $38,456, is 4 percent lower than it was in 2011. This poverty near Amazon facilities is not just an inland-California phenomenon—according to a report by the left-leaning group Policy Matters Ohio, one in 10 Amazon employees in Ohio is on food stamps.

The arrival of Amazon has been bittersweet for people like Gabriel Alvarado, 35. He started working at Amazon’s San Bernardino distribution center in 2013, making $12 an hour, hoping that the job would help him support his new wife and two stepdaughters. Amazon proved a stressful place to work, with managers chewing out employees for not moving fast enough, he told me, which was tough to put up with for meager pay. (An Amazon spokeswoman, Nina Lindsey, told me that, like most companies, Amazon has performance expectations, but that it supports people not performing with dedicated coaches to help them improve.)

Meanwhile, Gabriel watched as his 39-year-old brother Jose worked across the street, doing the same type of job at a warehouse for the grocery chain Stater Brothers. The 1,000 workers there are unionized and get full medical benefits, pensions, and retiree medical benefits. Wages start at $26 an hour, but many workers make a lot more than that because Stater Brothers operates an incentive program in which people who grab orders—doing similar tasks to workers at Amazon—are rewarded if they go faster than the average speed. Jose Alvarado is able to support a wife and four children on his Stater Brothers salary. When his son was diagnosed with a rare form of anemia, his insurance covered everything.

Though Gabriel was doing the same type of work at Amazon, he had to shell out more money for health care, and made a lot less money. “I saw my brother doing the same type of work, but moneywise, he had better credit, he could afford more, while I was barely getting by,” Gabriel told me. He has tried to get a job with Stater Brothers to no avail, and says there are few other local options but at Amazon or at companies that work for Amazon. In 2016, he used Amazon’s tuition reimbursement to get his commercial driving license, attending school on the weekends while working during the week. But the best job he could find was working for a third-party contractor, driving a truck for Amazon. “It’s either Amazon or nothing,” he told me.

The lack of other opportunities for people like Gabriel Alvarado illuminates the problem these communities face when deciding to offer tax breaks and incentives to compete for Amazon to build warehouses in their towns. If these places don’t get a new Amazon facility, they won’t instead get companies like Stater Brothers that are willing to come in and pay double or triple the minimum wage for jobs that don’t require a college education. For many places, the choice is not between Amazon or another, better employer. The choice, instead, is Amazon or nothing. “There’s this way in which Amazon’s warehouses are perceived to be a good thing for a community, but that’s only because the context in which they are being proposed and built is so devoid of better opportunities,” says Stacy Mitchell, the co-director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a nonprofit that advocates for sustainable community development. “It’s an indicator of how badly our economy is doing in terms of providing meaningful and valuable opportunities for people.”

Morris, the former mayor of San Bernardino, told me that in 2012, Amazon seemed like a lifesaver. San Bernardino’s unemployment rate was at 15 percent, home values had fallen 57 percent since 2007, and the city, facing a $45 million budget shortfall, would file for bankruptcy in August of that year. “At the point they came in, any job is a good job,” he said. But the jobs the company is offering are indicative of how the economy has changed in San Bernardino in the past few decades. “To a certain extent, based on the history, it’s a step down for families,” he said. The jobs that used to dominate San Bernardino were unionized ones with good benefits, at the Kaiser steel mill, the Santa Fe railroad maintenance yard, and the Norton Air Force Base. Now, jobs like the ones Amazon creates pay less and aren’t unionized, and require multiple members of a household to work, often more than one job.

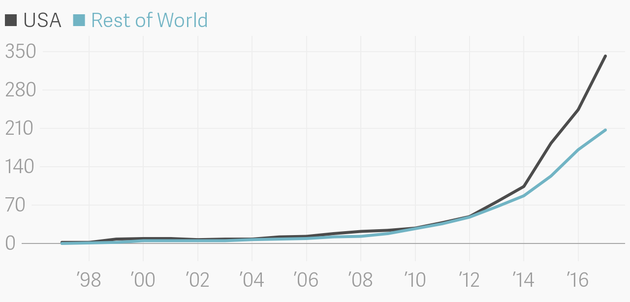

As Amazon continues to grow at a rapid clip, more communities are in the same position as San Bernardino—desperate to attract new jobs, even ones that pale in comparison to past opportunities, in the absence of anything else. Although efforts to recruit new distribution centers garner less national attention than the race to attract Amazon’s HQ2— its second corporate headquarters, where the company is expected to add as many as 50,000 jobs—when added up, these other facilities create a large number of jobs. Amazon now has 342 facilities, including fulfillment centers, Prime hubs, and sortation centers, in the United States, up from 18 in 2007, according to MWPVL International, a supply-chain and logistics consulting firm. Amazon employed 180,000 people in the United States in 2016, and said last year that it planned to add more than 100,000 full-time, full-benefit jobs by mid-2018. The company is a microcosm of the growing logistics industry, which is booming as more and more people order goods online. The company is growing even in places where it already has a substantial presence: Although it has eight fulfillment centers near San Bernardino, Amazon recently announced it was adding two more facilities nearby, creating 2,000 more jobs.

Amazon allows visitors to tour one of its warehouses in San Bernardino, and I went late last year to try and understand how distribution centers work. The warehouse, called ONT2 internally, is a vast complex, where clean concrete floors stretch out in all directions covering the distance of about 16 football fields. Bright yellow posts divide the different sections of the building, where people unpack shipments, load shelves, unload shelves, and pack everything from puzzles to lightbulbs into Amazon’s ubiquitous brown boxes. Conveyor belts covering several miles whir throughout the facility, moving goods among floors.

For local residents, starting work in this facility or one like it can seem like a blessing. At around $12 an hour, 40 hours a week, full-time jobs pay higher than many others in the region, and the benefits are also better than many other jobs in the industry. But workers are required to be on their feet all day, and receive scant time for bathroom breaks or lunch. They’re pressured to meet certain production goals and are penalized by getting “written up”—the first step in getting fired—for not meeting them, they say. They’re also allowed very little time off, and written up if they go over a certain amount of time off, these workers say, even if they get sick. This is according to in-depth conversations I’ve had with 10 current and former Amazon employees. These employees work in the San Bernardino facility, as well as Amazon distribution and sortation centers in Moreno Valley, California; Jeffersonville, Indiana; and Kent, Washington. Amazon has been sued in the past by part-time, contract workers. All but one of the people I interviewed were full-time employees, not contract workers, and they didn’t think working directly for Amazon was so great, either. As one worker, John Burgett, a current employee in Indiana who has detailed his experiences on the blog Amazon Emancipatory, told me, “It’s very physically and emotionally grueling. They’re walking a fine line in the community—everybody knows someone who’s worked there, and no one says it’s a good place to work.”

Many people who start out at Amazon warehouses begin as “pickers.” These are the people who walk through the enormous aisles in the Amazon warehouses where goods are stored, and, reading information from a handheld scanner, put items that have been ordered online into yellow bins, called totes. The scanner gives pickers an amount of time to “pick” an item based on where it is stored, and blue bars on the scanner count down the amount of time they have left to complete the task. Slightly more desirable than picking is stowing. “Stowers” take bins of items that have been shipped to Amazon and store them on the shelves for the pickers to grab when ordered. Other employees work as “packers.” They take items from yellow totes, scan them, grab a box and packing tape, the size of which is recommended by a computer, and pack individual customers’ orders, putting the finished boxes on a fast-moving conveyor belt.

The workers I talked to said that the problem with these jobs is not just that they’re physical or monotonous—which they are—but, rather, that Amazon puts an incredible amount of pressure on people to continue to work faster and faster. Many of the employees mentioned the fear of being “written up” and losing their jobs, which will thrust them into other low-paid jobs with fewer benefits. If pickers don’t grab an item in a certain amount of time, they get written up. If they take too long a bathroom break, they get written up. If they’re not walking as fast or performing as well as the majority of employees, they get written up. “You constantly feel like, ‘I’m not doing enough, I need to do a little more,’ and that’s their business model,” Burgett said. “The constant trying to chase your rate, trying to stay ahead of being written up—it affects you psychologically.” This pressure is not limited to warehouse workers; a 2015 New York Times story detailed a corporate culture where white-collar workers were pushed psychologically as well.

Another man, a former carpenter who works in the stow department in Moreno Valley and didn’t want his name used because he still works for Amazon, said that without warning, Amazon changed the amount of time workers had to stow an item from six minutes to four minutes and 12 seconds. “They make it like the Hunger Games,” he said. “That’s what we actually call it.” Workers are competing against an average time, and so they are, in essence, competing against each other. Those who can’t keep up are written up and then fired, he said.

Another Moreno Valley employee, who has been a picker at Amazon for two and a half years, says the company constantly sends messages to workers’ scanners telling them to work faster. They’ll run competitions such as a “Power Hour” in which workers are encouraged to work as hard as they can for a prize. One recent prize was a cookie. Another time, the winner of Power Hour would be entered into a raffle to win a gift card. “I don’t want a cookie or a gift card. I’ll take it, but I’d rather a living wage. Or not being timed when you’re sitting on the toilet,” said the man, who lives with his father because he and his girlfriend can’t afford their own place, and didn’t want his name used because he hopes to get promoted at Amazon.

One woman I talked to in Moreno Valley, who didn’t want her name used because she is in the process of suing Amazon, said that working at the company strained her heart and caused psychological problems that she’s still dealing with. She was written up for not working enough hours after she went to the emergency room because of her heart problem, she says. On the other hand, she says, she made enough money at Amazon to buy her first new car. “That’s what makes people not want to quit—the pay,” she said. “People say, ‘You can treat me any type of way, since this is the best money we can get out here in Moreno Valley.’”

I did talk to one Amazon worker who started as a picker and made his way up to management. David Koneck, now 34 years old, was one of the first workers hired by Amazon when the San Bernardino facility first opened. At the time, Koneck, who graduated from high school but not from college, was running a company that administered diagnostic tests for high-school students. That job was unstable in the aftermath of recession-era budget cuts, so when Amazon announced it was hiring, he applied right away, attracted by the benefits, such as health insurance and a program that allowed him and his wife to share paid leave when they had their first child. He started by working as a picker on the night shift, and within nine months was promoted. Both were good jobs, he told me—he and his wife bought their first house, in Hesperia, California, while he was an hourly associate. (Public records show it cost $182,500.) The company gave him lots of opportunities to move up and receive training in different areas, he said. After two years with the company, he was promoted again, and moved into management. Today, he’s an operations manager. “I wanted to come in here and achieve as much as I could, and nothing has stood in my way,” he told me. “It’s been nothing but positive support for me.” He’s now trying to help other hourly associates move up the Amazon ladder.

Amazon says that many employees have experiences similar to Koneck’s. At one Kentucky facility, according to Lindsey, the Amazon spokeswoman, more than 100 employees have been with Amazon for more than 15 years. But the workers I talked to say few employees make it more than a year. Their theory was that Amazon begins to cull employees when they are reaching the two-year mark, at which point their stock options would vest. (Lindsey says it is “strongly” in Amazon’s interest to retain employees to provide them with opportunities to develop, because the company is growing so quickly.) The former carpenter says employees call workers approaching the two-year mark “the walking dead” because they are working hard not to get fired, but many of them will be. “Very few Tier One employees ever make it to two years of continuous service,” Burgett writes. Anecdotally, he estimates that about 5 percent of new hires receive vested stock shares. “There are only two options,” Gabriel Alvarado told me. “You get tired—tired of trying to make rate every week, tired of the write-ups—or you get fired because you didn’t make quota or run out of unpaid time off.” Associates receive 10 hours of paid time off when they begin, Lindsey told me, which is essentially one day off. Most associates work four 10-hour shifts a week and only accrue a small amount of paid time off every pay period, workers said, which means it can take months to get another day off.

“When we’re thinking about Amazon coming in and creating a huge number of jobs, what’s the quality of jobs? We should also be really examining that,” says Beth Gutelius, a researcher at the Great Cities Institute at University of Illinois at Chicago who wrote her dissertation about the warehouse industry in the Chicago suburbs. “Sometimes these more exurban areas are really desperate for jobs, and you can’t deny that, but places do have to really think hard about it.”

Current officials in San Bernardino maintain that Amazon’s presence has been a positive one. The new mayor, R. Carey Davis, told me that the city has seen a number of benefits since Amazon opened its first warehouse. The company has contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars to local schools and charities, for example. “The city of San Bernardino has found that Amazon has been a very good neighbor and private partner for the city of San Bernardino,” he said. Amazon’s presence has signaled to other cities that San Bernardino is a good place to locate, with qualified workers, and an efficient city government, says Mike Burrows, the executive director of the Inland Valley Development Agency and the San Bernardino International Airport Authority. It’s helped create jobs on the land once used by the Norton Air Force Base until it closed two decades ago. Amazon recently surpassed Stater Brothers, which had been the largest employer on the land formerly occupied by the air force base with 2,000 employees, according to the Inland Valley Development Agency. Now, Amazon has 4,900 employees in San Bernardino.

The arrival of Amazon may have been good for other businesses in the Inland Empire, but its effects on individual residents seem less positive. While warehousing and storage was one of the fastest-growing sectors in the Inland Empire over the past decade, adding 35,800 jobs, the area also has the lowest annual private-sector average wage out of the country’s 50 largest metropolitan areas. A report from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance found that Amazon paid 11 percent less than the average warehouse in the Inland Empire; a similar analysis by The Economist found that workers earn about 10 percent less in areas where Amazon operates than similar workers employed elsewhere.

Amazon has the potential to be the shining knight that city officials hope it will be when it opens in their cities. Amazon could become more like Stater Brothers—paying workers more, incentivizing efficiency rather than punishing workers who fall behind, supporting efforts to form a union. It could treat workers like Jose Alvarado is treated. After 11 years at Stater Brothers, Alvarado, who also plays on the company softball team, has no plans to leave. “I’m able to support my whole family and live a really good life,” he told me, a stark contrast to his brother.

But that would require a wholesale change in Amazon’s business practices, which would probably not sit well with consumers who have become accustomed to free shipping and cheap goods. (Amazon is losing money on its e-commerce operations, which are subsidized by other parts of its business.) “More opportunity for folks with less education is generally a good thing,” says Gutelius, the Chicago researcher. “It would be a much better thing if the job quality were better, if there were some real kind of job ladder over time.”

Efforts to get Amazon to change its labor practices have been unsuccessful thus far. Randy Korgan, the business representative and director of the Teamsters Local 63, which represents the Stater Brothers employees, told me that his office frequently gets calls from Amazon employees wanting to organize. But organizing is difficult because there’s so much turnover at Amazon facilities and because people fear losing their jobs if they speak up. Burgett, the Indiana Amazon worker, repeatedly tried to organize his facility, he told me. The turnover was so high that it was difficult to get people to commit to a union campaign. The temps at Amazon are too focused on getting a full-time job to join a union, he said, and the full-time employees don’t stick around long enough to join. He worked with both the local SEIU and then the Teamsters to start an organizing drive, but could never get any traction. He told me that whenever Amazon hears rumors of a union drive, the company calls a special “all hands” meeting to explain why a union wouldn’t be good for the facility. (Lindsey said that Amazon has an open-door policy that encourages associates to bring concerns directly to the management team. “We firmly believe this direct connection is the most effective way to understand and respond to the needs of our workforce,” she wrote, in an email.)

Gabriel Alvarado, too, said he talked with some friends about starting a union in San Bernardino, after contrasting his situation with that of his brother. Amazon soon called a meeting and asked workers what they wanted to make their jobs better, he says, but few of the workers’ suggestions were carried out. No Amazon warehouse has been organized thus far. In 2014, workers at an Amazon warehouse in Middletown, Delaware, voted 21–6 against joining the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers. Burgett thinks these outcomes are the result of, what he calls in his blog, Amazon's “well-oiled and well-financed anti-union machinery.”

There are many other reasons communities might pause before welcoming an Amazon warehouse. But many still welcome the company, believing that it’s better to have some jobs in the new Amazon economy than no jobs at all. Fresno, another economically depressed city in California, offered Amazon $15.3 million in property tax rebates and $750,000 in sales tax rebates to locate a facility there, an offer Amazon was happy to take up. Amazon won $23 million in local tax incentives over two years to open distribution centers in three Texas cities. The company has received $48 million in state, county, and city financial incentives to build facilities in Florida.

This race to the bottom may be preventing cities from holding Amazon—or other logistics companies—accountable. After all, most communities aren’t in a position to negotiate with Amazon to ensure that workers will be treated well. Last year, I interviewed Michael Tubbs, the mayor of Stockton, California, shortly after Amazon announced in August that it was locating a distribution center and 1,000 jobs in the inland city in Northern California. Tubbs is young and progressive, but still told me that Stockton had little power over Amazon. “I don’t think the city of Stockton currently, with an unemployment rate double the state average, is in a position to make a ton of demands on companies who can go anywhere,” he told me. San Bernardino had tried to negotiate that it would get a portion of the sales tax of all the goods that came through its distribution center, but ultimately spent money to build roads and provide police and fire protection to the warehouse and does not get any sales-tax revenues from the warehouse, Morris said. (The state of California, not Amazon, quashed the deal.)

As the race for Amazon’s HQ2 shows, other cities competing for Amazon jobs offer up all sorts of concessions, and worry that in passing any wage and hour mandates, they’ll lose the jobs. “I think often, local policymakers are really eager to get companies in, they want employment, but they don’t necessarily give a lot of stipulations about how many of these workers are temps, how many are paid a living wage,” Ellen Reese, chair of the labor-studies program at the University of California, Riverside, told me.

It’s true that cities desperate for jobs may find it difficult to attract companies if they pass minimum-wage mandates or other labor laws. But the alternative, it seems, is jobs that don’t create a middle-class lifestyle for residents, which in turn affects local spending, the housing market, and the tax base, and leads to a poor standard of living. Many cities, San Bernardino included, are calculating that any job creation is good news. They may soon find that with Amazon, that calculation does not apply.