Just after midday on Tuesday 12 February, word came down that the verdict was ready in what had been widely described as the trial of the century. “United States of America v Joaquín Guzmán Loera” had lasted approximately three months – it took prosecutors that long to present what they described as “an avalanche” of evidence, which had taken more than a decade to compile. The government called 56 witnesses, the defence called only one: an FBI agent, who finished testifying within an hour.

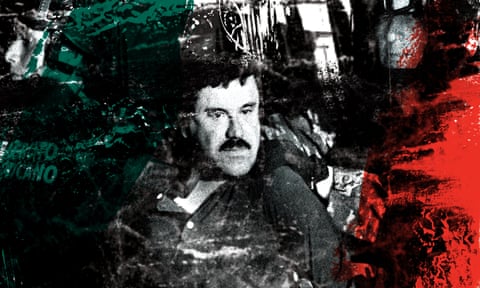

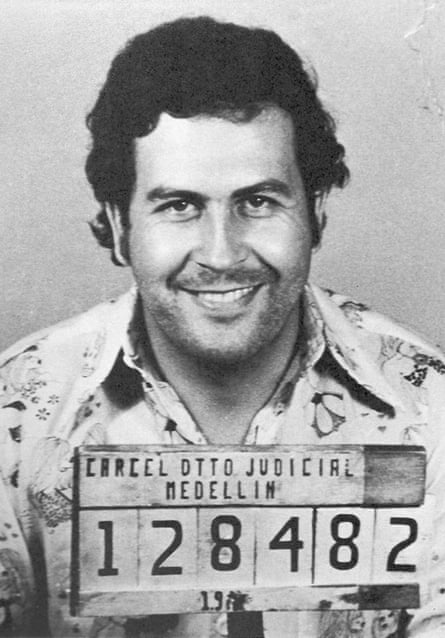

There was little expectation that Guzmán would mount a convincing defence. The diminutive 61-year-old (his nickname, El Chapo, means “shorty” in Spanish) was known around the world as a leader of Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel, and the most high-profile drug kingpin since Pablo Escobar. In addition to smuggling thousands of tonnes of cocaine, heroin, marijuana and synthetic narcotics across the US-Mexico border, he had successfully pulled off two dramatic escapes from prisons in Mexico. He has been the subject of dozens of books, two popular TV series and, in 2009, was included in Forbes magazine’s list of billionaires. The following year, that same magazine named Guzmán one of the world’s most-wanted fugitives, second to only Osama bin Laden. As Guzmán’s lawyers liked to tell anybody who would listen, even before their client set foot in Brooklyn, he had already been convicted in the court of public opinion.

When he was captured by Mexican marines on 8 January 2016, Guzmán became the prize feather in the cap of the country’s law enforcement. Barack Obama called Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto to congratulate him on the arrest, and in a move that could be interpreted either as a parting gift to Obama or a peace offering to his successor, Guzmán was extradited to New York on 19 January 2017, a day before Trump took office. Jack Riley, a retired Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) chief who recently published a book about his role in Guzmán’s arrest, told me that in the view of US authorities, catching El Chapo was an important warning to criminals around the world. Regardless of where you are, if you are breaking American laws, “eventually, we’re going to get you”.

Americans spend around $109bn on illegal drugs each year, and Bloomberg estimates that the Sinaloa cartel makes at least $11bn in annual sales to the US. But while Mexican cartels regularly appear in the US media, most people are unfamiliar with the circumstances that contributed to their rise. It is not common knowledge that Mexico launched its own war on drugs in the mid-2000s, or that the biggest cartels are sophisticated operations worth billions of dollars. Nor are many people aware that cartels are increasingly responsible for fentanyl, a form of synthetic heroin, entering the US. In an address to the media after the verdict was handed down, US government officials emphasised this point and the role of illegal fentanyl in perpetuating the opioids crisis.

While the workings of his business may be a mystery, Americans have heard of El Chapo. By the time he appeared in court in 2018, he was a late-night TV punchline, a symbol of extreme wealth and an escape artist with a talent for leaving law enforcement with their hands empty.

At the trial, Guzmán was found guilty of all charges against him, including the most serious – having engaged in a continuing criminal enterprise. He will be sentenced at the end of June, and is almost certain to be jailed for life. His lawyers are seeking a retrial on the basis of jury misconduct, but the chances of that happening are slim.

When I was in Mexico City this spring, a month after the verdict, talk of the trial had already died down. Guzmán’s image had mostly disappeared from the magazine covers on display at the news kiosks that dot the streets of the capital. While people could still name the Sinaloa cartel’s leaders and lieutenants, they were more interested in the newer cartels, such as Jalisco Nueva Generación or the local La Unión. Many people didn’t want to discuss El Chapo at all. “Narco fatigue” – the exhaustion that comes with being oversaturated by news and pop culture about the drug trade – had long ago set in. Over the past 13 years, Mexico’s internal war on drugs has dominated the media, resulted in the deaths of over 100,000 people and failed to stop narcotrafficking.

Guzmán’s arrest did not magically rid Mexico, or the US, of violence or drugs. Above all, his trial demonstrated how disposable any single person is in the larger machinations of the narco-state. There has never been a clear definition of what exactly constitutes a cartel, and as smaller, more transient gangs replace larger organisations, going after leaders like Guzmán seems increasingly pointless. Rather than reducing the levels of violence and trafficking in Mexico, that approach – the so-called kingpin strategy, employed by Mexico and the US – has enabled new forms of crime to flourish. As Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, Chapo’s longtime partner, said in 2010 in a rare interview with the Mexican news magazine El Proceso, the problem of narcos isn’t going away: “As soon as capos are locked up, killed or extradited, their replacements are already around.”

Since the early 1990s, the US has targeted cartels via their leaders. It is a fairly straightforward idea: take out the head of an illegal organisation and the rest will collapse. The approach was developed to bring down the Colombian cartels, and in that case, it had some success. When Pablo Escobar was shot to death by Colombian police in 1993, his cartel went down with him.

But even as the structures of organised crime have evolved, US law enforcement has generally stuck to this top-down model. If they are not killing drug lords, they are using the American judicial system to make examples of them. Since 2001, when Mexico’s supreme court agreed to allow the extradition of criminals so long as they would not face the death penalty or life in prison (this ruling was amended four years later to permit life sentences), dozens of narcotraffickers have been extradited to the US, including members of the Tijuana, Beltrán-Leyva, Sinaloa and Los Zetas cartels. If Guzmán ends up in the supermax prison in Florence, Colorado, as he is expected to, he will share the facility with former Gulf cartel leader Osiel Cárdenas Guillén.

While Sinaloa has historically been, and still remains, Mexico’s most powerful cartel, the world it came up in no longer exists. Between the early 90s and the mid-2000s, the Sinaloa, Tijuana, Juárez and Gulf organisations were mini-monopolies, with borders that more or less stayed the same. Then, with the start of Mexico’s drug war in 2006, that arrangement started to fall apart. As Mexican and American authorities took out cartel leaders, groups fractured and new ones emerged.

Previously, the Zetas, whose leaders came from the special forces of the Mexican army, had been a mercenary group in the employ of the Gulf cartel. Now they became an autonomous organisation. Jalisco Nueva Generación, which had been linked to Sinaloa, morphed into one of Mexico’s most ferocious cartels. Splinter groups and gangs that had originated in prisons or as local militias began to gain power.

This fragmentation altered the way cartels do business. To distinguish themselves in a crowded field, the new groups pioneered the use of sadistic, headline-grabbing violence. They also diversified. Whereas an old-school cartel might have once only sold drugs, the upstarts are expanding into different forms of crime. The Zetas are notorious for stealing petrol from nationalised pipelines and selling it on the black market – a business that Sinaloa previously dominated, as journalist Ana Lilia Peréz documented in her book El Cartel Negro. The Santa Rosa de Lima cartel also specialises in petrol theft, known nationally as huachicol. Protection rackets are common. And cartels are kidnapping and extorting migrants on their way to the US border. In 2010, the bodies of 72 Central American migrants were found on a ranch in the north-eastern state of Tamaulipas. According to the lone survivor of the massacre, an 18-year-old Ecuadorian, the Zetas murdered the group when they refused to either pay for their freedom or serve as cartel hitmen.

At the same time, older cartels are expanding and decentralising. According to law and economics scholar Edgardo Buscaglia, Sinaloa has a presence in 54 countries and Jalisco Nueva Generación, one of Mexico’s fastest growing cartels, is said to have branched out throughout the Americas. Maintaining such operations requires a vast and diverse network of legal fronts and elaborate systems of money-laundering. To illustrate this point, the journalist Diego Osorno recently noted that the most popular brand of milk in Sinaloa is made by a company owned by Guzmán’s colleague El Mayo. The Sinaloa cartel operates on such a large scale – connecting manufacturers and distributors, bankers and businesses and extracting money at each step – that there is no longer a single face of the organisation. Buscaglia told me that that if I wanted to see the “sophisticated” side of the Sinaloa cartel, I should visit a particular gated community in Argentina. I wouldn’t find any gangsters flashing guns, he clarified, only the wealthy managers of the cartel’s legal operations in that country.

This fragmentation also means that cartels and low-level gangs are harder to police and prosecute. Paradoxically, there are also more mini-kingpins to capture. And once they are in the US, narcotraffickers can cut plea deals and help prosecutors capture their former bosses and colleagues. Captured Mexican narcos generally have few qualms about cooperating. A good outcome might mean a radically reduced sentence and half their fortune waiting for them on release. An even better outcome might resemble that of Andrés López López, one of the former leaders of Colombia’s Norte del Valle cartel. In 2006, López had an 11-year sentence knocked down to 20 months after working with authorities. Now based in Miami, he has written three books about trafficking, one of which was adapted into a wildly successful TV show in Latin America. His most recent book, which was also optioned for television, is a biography of El Chapo.

I first went to the Guzmán trial in early December, and began to go more frequently as a broader picture of cartel operations came into focus. In building the case, prosecutors approached it like a classic mafia roll-up, offering leniency to each captured narco and gradually working their way up the chain until they reached Guzmán. As Miami defence attorney Joaquin Perez, who has represented many extradited narcotraffickers, told me, it was a “significant effort for a fait accompli”.

It also made for good theatre. There were accounts of diamond-encrusted guns and cocaine stash houses in fancy Brooklyn neighbourhoods, million-dollar smuggling submarines capable of evading police radars and elaborate schemes to outwit US law enforcement. Week after week, witnesses described in intricate detail the inner workings of la oficina (the internal nickname for the cartel): its lavish displays of violence and wealth, its complex transportation networks and how Mexican authorities were systematically paid off. In search of material, screenwriters and actors showed up at the trial.

Tabloid headlines advertised the “wacky world” of the trial, and newspapers ran lists of its most bizarre disclosures. By the time the prosecution rested after 11 weeks of testimony, jurors had heard from Juan Carlos Ramírez Abadía, AKA “Chupeta” (lollipop), a formerly handsome Colombian kingpin who had undergone such extensive plastic surgery to stay in hiding that his face looked like a rubber Halloween mask; Jorge and Alex Cifuentes-Villa, brothers and Colombian career criminals who had worked closely with Guzmán; and Lucero Guadalupe Sánchez López, Guzmán’s mistress and one-time accomplice. Jorge Cifuentes-Villa described attempting to kill a man with a poisoned sandwich, and Alex told the jury that Guzmán had allegedly boasted about bribing former president Peña Nieto for $100m. (Peña Nieto’s former chief of staff described this claim as “false, defamatory and absurd”.)

Yet to many of the seasoned narco corresponsales, the trial offered few newsworthy revelations. “Everything that was astonishing to American audiences was not to Mexicans,” said David Brooks, the US correspondent for the progressive Mexican newspaper La Jornada. Mexican readers were no longer scandalised by accounts of extreme wealth or violence. Besides sex and infidelity, which were of universal interest, Brooks told me that the stories that landed with his readers were ones that named names, confirming that long-suspected officials had taken bribes or worked both sides of the table.

The more I spoke with the Mexican journalists, the more I became aware of the underlying issues going unaddressed in the courtroom. There were few mentions of the consequences of the war on drugs, which had led to the deaths of thousands of Mexicans. And because it was being held in the US, some saw the case as a finger in the eye of Mexican sovereignty, a serious injury to national pride. (There was some irritation over the fact that Guzmán was being tried, as several journalists grumbled, in a court where the judge couldn’t properly pronounce his name.)

At the same time, nobody seemed to think the trial should have been held in Mexico, where the police and judicial systems were too weak to guarantee that Guzmán wouldn’t escape jail for a third time. Again and again, I spoke with journalists and academics who described corruption in Mexico as something like a tide, a force that grew steadily and drew everything towards it. Police were underpaid, crime was lucrative and the government was compromised by the cartels. Political corruption, usually through campaign contributions or by laundering money through public procurement projects, is standard. When I asked people in Mexico City about the enthusiasm surrounding the new president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who took office in December 2018, I often heard that his willingness to take on corruption was his main selling point.

The basic problem in Mexico, Buscaglia told me, is that nobody is policing the courts. Mexico doesn’t audit judges or prosecutors, and lacks independent monitoring agencies. Despite recent reforms to the criminal justice system, Buscaglia does not think that Mexico currently has the capacity or political will to execute major organised crime cases like Italy did with its famous “Maxi trial” in the late 1980s. There, Sicilian prosecutors indicted 475 mafiosi over a six-year period. That, he added, indicates the most significant difference between Mexico and Italy: organised crime didn’t infiltrate the Mexican state – it helped shape it. “Politics in Mexico,” Buscaglia likes to tell people, “is the most sophisticated form of organised crime.”

Did the state shape the cartels, or was it the other way around? The standard narrative is that the cartels infiltrated the state, blurring the lines between police, politicians and traffickers. Others contend that government authorities exaggerated the power of the cartels in order to blame them for their own transgressions. It is possible some version of each is true. Either way, there is no single force in control.

There has never been a hard divide between the state and traffickers in Mexico. In the 1920s, farmers began growing poppy to meet US demand for opium, and after the second world war, representatives of what would become Mexico’s Institutional Revolutionary party (PRI) were rumoured to have made handshake deals with smugglers, allowing them to export illicit crops across the border in exchange for a cut of the profits. The PRI was the de facto government for most of the 20th century – the novelist Mario Vargas Llosa once called Mexico under the PRI “the perfect dictatorship” – and during its tenure, politicians generally took a lax attitude towards the drug trade, regarding drugs as more of a health issue than a criminal one.

By the 1980s, narcos had solidified their power by divvying up trafficking routes and letting groups run their own territories. At the time cocaine trafficking was starting to become big business in Mexico. When the US DEA began targeting Colombian cocaine distribution routes between the Caribbean and Miami, the cartels had found an alternative in the Mexican “trampoline”. Traffickers started moving shipments across the porous US-Mexico border, and American officials redirected their attention to Mexico. From 1985 onwards, US operations in Mexico became more aggressive, following the kidnap, torture and murder of a DEA agent by the Guadalajara cartel. With the cold war receding, drugs replaced communism as the enemy No 1 of the American people.

The Americans did not find the Mexican authorities the most co-operative of partners in the “war on drugs”. By the 80s and 90s, writes the sociologist Luis Alejandro Astorga Almanza, “it was practically impossible for society to ignore the unbreakable links between police and traffickers”. Particularly in states such as Tamaulipas, cops would moonlight as traffickers – and traffickers as cops – with the tacit blessing of local authorities and elites. “Various governmental structures seem to have been born captured by the illicit interests of their own creators,” writes Carlos Antonio Flores Peréz, a social anthropologist who studies the institutional protection of the drug trade. US army intelligence cables from the 80s and early 90s reveal that American officials were fully aware that all over Mexico, officials, politicians and state and federal police were in on the take.

In April 1989, Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo, the former police officer who founded the infamous Guadalajara cartel, was arrested, but like Escobar, he continued to run his cartel from prison. That year, his most powerful lieutenants – one of whom was a young Guzmán – assembled in Acapulco and were each assigned a territory. El Chapo and El Mayo took the Pacific coast. This kingmaker moment ushered in a new era, and preceded yet another big shift. Instead of continuing to accept cash from weakened Colombian suppliers, Mexican narcos began demanding payment in cocaine so they could go into business on their own. Before long, they went from being couriers to distributors, which was far more profitable, and overtook their former employers as the world’s biggest traffickers.

While agreements between cartels and Mexican authorities had previously kept violence between the two at bay, by the late 80s these relationships were strained. With the US putting more pressure on the Mexican government to target traffickers, the old arrangements dissolved. Under these new circumstances, violence became common among gangs, writes Sinaloan historian Froylán Enciso, and “a way of confronting the government”.

Still, it rarely spilled into public view. So the country was stunned when in May 1993, a Mexican cardinal was killed in a shootout between the Tijuana and Sinaloa cartels at Guadalajara airport. Although it was later discovered that Tijuana sicarios had mistaken the cardinal’s car for Guzmán’s – they were retaliating for a Sinaloa attack that killed nine Tijuana members – he was initially blamed. A nationwide manhunt was called, and with Guzmán splashed all over the papers, he became a household name in Mexico.

In June 1993, he was captured in Guatemala, extradited to Mexico and later sentenced to 20 years in jail for drug trafficking and murder. But for the next eight years, until he escaped in 2001 – allegedly hidden in a laundry cart pushed by a guard – Guzmán, like Félix Gallardo before him, continued to run his business from jail without any difficulties.

In the early 2000s, after Guzmán’s first escape from jail, Sinaloa began to expand. The organisation moved into the markets for meth and fentanyl and, as opioid addiction gained momentum in the US, Guzmán approached it like a shrewd businessman. According to Jack Riley, the former DEA head in Chicago, between 2010 and 2014, the cartel “increased the flow of Colombian and Mexican heroin because [Guzmán] saw the prescription drug problem taking over”.

While this pattern played out across the US, Sinaloa’s power and logistical strength were concentrated in Chicago, the main hub from which they distributed drugs around the country. Cartel operations were so well organised, said Riley, that “you could hit a house with 50 kilos of heroin in it, and two doors down you could hit a house with $5m in it, and neither of the people running the houses even knew the other existed”.

Even as Sinaloa grew, Mexico was relatively peaceful. From the 1990s until 2006, Mexico’s homicide rate fell by nearly half, reaching the lowest levels in its history. Then, in late 2006, everything changed. Just over a week after the conservative Felipe Calderón took office, following a bitterly controversial election that he won by a margin of just 0.6%, he declared an internal war on drugs, sending 6,500 troops into his home state of Michoacán. To his critics, this new war on drugs looked like a bid to divert attention from accusations of election fraud.

Calderón’s announcement initiated what would become one of the deadliest periods in Mexican history. With billions in funding from the US, Calderón pursued his own version of the kingpin strategy, deploying the military to fight cartels and targeting their leaders. During his six-year tenure, 25 of Mexico’s “most wanted” – two-thirds of the entire list – were arrested or killed. As cartels pushed back, extortion and kidnappings spiked, and the number of homicides reached an average of 20,000 a year. “In this new atmosphere of fear,” wrote novelist Juan Villoro in an essay about the era, “10,000 companies offer security services and 3,000 people have had chips inserted under their skin so they can be located if they’re kidnapped”.

Despite this violence, Sinaloa seemed to receive less attention from the authorities than other cartels. An investigation by the US broadcaster National Public Radio (NPR) reported that between December 2006 and May 2010, Sinaloa members were arrested at significantly lower rates than those of rival groups. A congressman from Sinaloa also told NPR that the government “has been fighting organised crime in many parts of the republic, but has not touched Sinaloa”. Explanations for this varied from low-level corruption in the armed forces to more elaborate conspiracies involving the government – accusations that Calderón told reporters were “totally unfounded”, naming various Sinaloa members that the government had arrested.

In the next general election, in 2012, the PRI retook power and Peña Nieto became president. Although his administration retreated from the kingpin strategy, in 2014, more than a decade after he had first escaped from prison, Guzmán was recaptured and sent to the maximum-security Altiplano federal prison. The following year, he escaped once again, before he was recaptured for the final time in 2016. “Mission complete,” tweeted Peña Nieto.

After a year of negotiations and intense international pressure, Guzmán was extradited to New York in January 2017. If his capture had any effect on the violence in Mexico, it wasn’t immediately positive: 2017 was the deadliest year in modern Mexican history, with a total of 23,101 homicides. It is not clear exactly how many of these deaths and disappearances were linked to organised crime, but scholars have noted that a culture of impunity certainly contributed to the violence. Less than 2% of homicide cases in Mexico result in indictments. By the time Peña Nieto left office in 2018, the number of people killed since 2006 had risen above 250,000, with a further 31,000 declared missing. Targeting leaders had fractured the cartel landscape, and new gangs were rushing in to fill the gaps.

Drug trafficking and cartel violence affect both the US and Mexico, but when it comes to addressing them, the US government has typically strongarmed Mexico into following its lead. Long before the overt bullying of the Trump administration, American officials were known to pay little heed to Mexican sovereignty. Yet even when US violations of that sovereignty pertained to the trial, they were rarely discussed in court.

One notable example was the “Fast and Furious” scandal, which the judge in Guzmán’s trial explicitly barred from mention on the grounds that it would confuse the jury. In this staggeringly ill-advised scheme, US law enforcement agents encouraged gun dealers in Arizona to sell to traffickers believed to be connected to the Mexican cartels, in order to track the weapons and see where they ended up. The first part of this plan succeeded. Between 2009 and 2011, more than 2,000 weapons were purchased in the “gunwalking” operation, and it erupted into the news when a border agent was killed with one. A congressional review later revealed that “ATF [the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives] leadership knew that Fast and Furious weapons were heading to the Sinaloa cartel, and Attorney General [Eric] Holder was sent several memos in 2010 notifying him that the Sinaloa cartel was buying them”. An estimated 150 injuries and homicides resulted from the programme, and one of the weapons, a Barrett .50-calibre rifle, was found in Guzmán’s hideout after he was last captured.

Even in less dramatic instances, the “business as usual” of international law enforcement is fraught. Writing for El Proceso, J Jesús Esquivel described the Guzmán trial as having exposed “betrayals, corruption, lies and regular violations of Mexican sovereignty by DEA agents”. Esquivel also zeroed in on cooperating witness deals that the justice department offered to certain traffickers, including Vicente Zambada Niebla, the son of El Mayo and Sinaloa’s heir apparent. “El Vicentillo” was one of the trial’s most anticipated witnesses. He was flown in from Chicago, where he had yet to be sentenced on his own trafficking charges, and took the stand in dark blue prison clothes. In a five-hour testimony that the New York Times described as a spectacular betrayal of his father and birthright, Zambada Niebla gave a detailed insider account of cartel workings, describing how the organisation spent at least $1m a month on bribes to police and politicians, and detailing a failed plot to use a government petrol tanker to transport South American cocaine to Mexico.

For taking the stand against his “compadre”, as he politely referred to Guzmán, the 44-year-old was promised a shorter sentence and a possible path to US citizenship. Others were given similar offers. The Cifuentes brothers, who sent tonnes of drugs to cities all over the US, may serve less than 15 years for their cooperation. Even Chupeta, the Colombian trafficker who confessed to having ordered the killings of 150 people – and to having personally shot one man in the face – may be free in 10-15 years for his testimony.

In his plea agreement, Zambada Niebla also agreed to forfeit $1.37bn (yes, billion) to the US government, although it is highly unlikely any money will actually change hands. Since narcos don’t purchase property or open bank accounts in their own names, it can be difficult to locate assets, and if the money is in Mexico, US authorities rarely bother to track it down. Of course, there is no public information about how many narcos are in witness protection, or whether those living under assumed identities have managed to recoup some of their former fortunes. But it is not far-fetched to assume this could happen: on 30 May, a federal judge in Chicago sentenced Vicentillo to 15 years in prison. With time served, this leaves him with five years to go, which may be further reduced for good behaviour.

Outside the courtroom, away from the trial, the US-Mexico relationship is also defined by a kind of mutual obliviousness on the part of each country’s citizens. David Brooks, the Jornada reporter, told me there is still “mass ignorance about what’s happening next door”. In Mexico, he observed, Trump coming to power “reinforced every stereotype of America for the past hundred years”. At the same time, while there are 36 million Mexican Americans in the US, Americans are generally ignorant of what’s happening below the border. One thing that has gone notably unnoticed, according to Brooks, is the victory of left populist López Obrador. Since he took office in December 2018, Mexico has entered “a moment of potential transformation”, which, if the new president follows through on his promises, could reshape the way Mexico deals with drug trafficking.

A month after the verdict, I met journalist Ioan Grillo in the middle-class area of Roma in Mexico City, several blocks from the house where Alfonso Cuarón had shot his Oscar-winning film, and next to a Sinaloan seafood restaurant. Grillo had recently written an opinion piece rejecting the idea that Guzmán’s conviction was a victory in the war on drugs. “To bring a real sense of justice, you’d need something like a war crimes tribunal,” he observed. Grillo was building on a point that had been made repeatedly by members of the Mexican press at the trial – the case did not seem not to acknowledge how the war on drugs led to thousands of deaths and profoundly altered Mexican society.

There were mixed feelings in Mexico, Grillo added – not about whether Guzmán should go to jail, but about what justice should look like, what closure his conviction could offer and what the whole trial ultimately meant. This was the biggest trial in a drug war that has lasted more than a decade, and it didn’t even take place in Mexico. No actionable evidence against any officials had emerged, and Grillo said most Mexicans were not particularly surprised to hear any of the corruption allegations that the case brought to the surface.

El Chapo’s capture did not have any impact on drug trafficking or consumption, and there is no reason to think his sentence will, either. In 2018, a DEA report found that drug overdoses in the US had hit record highs, and that cocaine and heroin use was on the rise. In Mexico, where drug use has historically been very low, the numbers are steadily climbing: in 2016, 9.9% of the population said they had tried illegal drugs, up from 4.1% in 2002. Moreover, under the leadership of El Mayo and Guzmán’s sons, Iván and Alfredo, Sinaloa has continued to operate. Just as the trial was ending, Arizona officials announced the largest fentanyl seizure in history from a truck coming from Sinaloa territory; and, in mid-April, a presidential candidate in Guatemala was arrested for accepting a bribe from the Sinaloa cartel in exchange for appointing their people to high-ranking government positions.

What is changing in Mexico is the nature of violence. Kate Linthicum, the Mexico City bureau chief of the Los Angeles Times, says that in the past several years she has watched violence become more localised in small gangs and contract criminals with shifting affiliations. This has corresponded with a rise in narcomenudeo, small-scale street trafficking and other forms of crime, including petrol theft. Because Mexico’s petrol industry is nationalised, the robberies cost the government more than $3bn a year. Since López Obrador made it one of his signature issues, petrol theft has become a front-page staple. The thieves are usually associated with local gangs or cartels, and are often assisted by Mexican Petroleum employees. At the beginning of January, López Obrador shut off Mexican Petroleum pipelines to stop smuggling, causing a national shortage that lasted for days. This enraged petrol cartels, but burnished his popularity: a national poll found that more than 80% of Mexicans approved of the move.

It is clear the public wants reform, but the question is whether López Obrador will be able to do anything about the corruption that has for so long hobbled the state, including parts of his own administration. Three days after Guzmán’s sentencing, López Obrador visited Badiraguato, the kingpin’s hometown. Guzmán is by no means a popular figure in Mexico, but in Sinaloa, one of the country’s most dangerous regions, T-shirts with his face on them are sold in markets and he is widely regarded as a local hero. In a state where the federal government is largely absent, El Chapo is credited (without any evidence) with building roads and providing social services. After he was apprehended for the second time in 2014, hundreds of people turned out to demand his release.

During his visit, López Obrador promised jobs to the town’s young people and vowed to make sure that they would not be obliged “to take antisocial paths”. That was four months ago. The jobs haven’t yet materialised, but it was the first time residents could recall a president visiting the region.

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, and sign up to the long read weekly email here.