/media/video/upload/Lead_Video-Highest_Res-final.mp4)

The Porch Pirate of Potrero Hill Can’t Believe It Came to This

When a longtime resident started stealing her neighbors’ Amazon packages, she entered a vortex of smart cameras, Nextdoor rants, and cellphone surveillance.

The first time Ganave Fairley got busted for stealing a neighbor’s Amazon package, she was just another porch thief unlucky to be caught on tape. In August 2016, a 30-something product marketing manager at Google, expecting some deliveries, got an iPhone ping from his porch surveillance camera as it recorded a black woman in a neon hoodie plucking some bundles off his San Francisco stoop. After arriving home that afternoon, the Googler got in his Subaru Impreza to hunt for any remnants strewn around the streets of his Potrero Hill neighborhood. Instead, he spotted Fairley herself, boarding a city bus, which he trailed while dialing 911. Minutes later, he watched responding police officers pull their cruiser in front of the bus and escort her off. The Googler, sitting nearby in his car, played the Nest Cam tape for them—Yep, it’s her—and the police pulled a $107.66 Apple Magic Keyboard from Fairley’s purse and black tar heroin from her coin pocket. The officers wrote Fairley a ticket with a court date a month later. “I thought it was just a ticket, and that was it,” Fairley said.

It was only about nine months later, in May 2017, when one of Fairley’s neighbors plastered photos of her, “Wanted”-style, on Nextdoor, that Fairley realized things were about to get worse. Nextdoor is an online ticker tape of homeowner and tenant concerns, and the grievances can be particularly telling in a city of Dickensian extremes like San Francisco, whose influx of tech wealth is pitting suburban expectations against urban realities. The city’s property-crime rate is among the highest in the United States. Nextdoor posts about dogs slurping from a public drinking fountain and Whole Foods overcharging again (“Be on guard”) show up alongside reports of smash-and-grab car break-ins, slashed tires, and an entire crime subgenre of “porch pirates,” the Artful Dodgers of the Amazon age.

Fairley and her neighbor do not agree—will likely never agree—on what happened in the minutes prior to the photos of Fairley going up on Nextdoor. Fairley has sworn that the boxes she picked up were from down the street, where they had been laid out for the taking, and that her 6-year-old daughter was helping to haul them to their home in the public housing down the block.

Julie Margett, a nurse who lives on the street, in a purple cottage with a rainbow gay-pride flag and a Black Lives Matter sign in the window, said she was leaving her garage and spotted Fairley coming down her neighbor’s stairs carrying boxes with various addresses on them. Surmising that they were stolen, she asked Fairley warily, in her British accent, “What are you doing?”

Fairley called her a racist (in fact, she still does) and told her she was in the middle of moving. “That was what was so disarming about her,” Margett told me. “Before you know it, she’s torn you to shreds and she’s off down the block.” Margett snapped photos of the mother-daughter haul act—in one, the young girl sticks her tongue out at the camera—and, after calling the police, uploaded them into a Nextdoor post: “Package thieves.”

So, Fairley told me two years later, sitting in an orange sweatsuit in a county-jail interview room, that was the real acceleration of the epic feud of Fairley v. Neighbors of Potrero Hill, a vortex of smart-cam clips, Nextdoor rants, and cellphone surveillance that would tug at the complexities of race and class relations in a liberal, gentrifying city. The clash would also expose a fraught debate about who is responsible, and who is to blame, for the city’s increasingly unlivable conditions. As Fairley says, “It just got bigger and bigger and bigger.”

Parts of Potrero Hill feel like the sort of charmed place where Amazon deliveries could sit undisturbed on your stoop. The hill’s western ridge, overlooking the city, is filled with cozy bungalows and Victorian houses that once were affordable for San Francisco’s working and artistic classes but have appreciated during the tech rush; now most of them sell for well over $1 million. The public hospital where Fairley was born is now named after Mark Zuckerberg.

Meanwhile, the hill’s eastern and southern flanks are still lined with decrepit 1940s-era bunkers of public housing between patches of scruffy grass and concrete patios. The unhoused have set up camp around the neighborhood too, the city’s homeless population having spiked 30 percent in the past two years. This sometimes has led to hostile and politically divisive clashes, like when a luxury auction house at the foot of Potrero turned its sprinklers on the tents clustered outdoors in 2016. (The auction house claimed that the sprinklers were meant to clean the building and sidewalks, and were “not intended to disrespect the homeless.”)

Still, some residents, like Margett, said they were attracted to the diversity in a city that is hemorrhaging people who don’t earn tech paychecks. Margett said Potrero welcomed her, a white woman and a proud lesbian sporting a Mohawk ponytail (“The pulse of the neighborhood, to me, is more important than petty crime”), and the neighbors have dealt with the glaring disparities in their own ways. Every week, Margett picks up donations from big-box stores to take to homeless shelters; she also puts them on the bench in front of her house, free for the taking. A union-leader neighbor, Jason Rosenbury, showed the person he suspected of stealing his succulent plants a Nest recording of the heist, and said he wouldn’t report it to the police if he got the plants back. Upon their return, he glued new pots to the concrete to avoid further strife. “I’m a full-blown socialist,” he told me, “but I’m also for law and order.”

When I visited Margett, she said that in her interaction with Fairley, the charged dynamic of “white-privileged homeowner” versus “someone who is barely making it” was not lost on her, yet she didn’t consider herself a bigot for calling out what she deduced was petty crime. “One is always so concerned about not wanting to appear that way, and then I’m second-guessing myself—Maybe I did leap to that conclusion because she’s African American,” she recalled. “But no! I know what I saw.”

On view out of Margett’s rear window, a redevelopment plan for Potrero’s public housing was under way. The run-down buildings are being razed, and the dwellers are being moved into fancy new buildings next to neighbors paying market rates, an upgrade that Fairley, who had at one point moved to a new unit when her old one became infested with mold, had been looking forward to.

Fairley is now 38, with close-cropped hair styled in braids. Among the family members’ names tattooed on her neck, back, and arm are those of her parents, next to praying hands; Fairley said she has forgiven them for her chaotic early years in Potrero, when they were addicted to drugs and she witnessed abuse. (She told me she prefers not to talk about the painful particulars.) When Fairley was 5 years old, social workers whisked her and her siblings to a great-aunt’s, where she told me she had a sheltered childhood: therapy, church, road trips to Yosemite. In middle school, she started flourishing at basketball and earned a scholarship to a Catholic high school. But a knee injury shut down the tuition aid, she said, and a transfer to public school introduced her to a rough crowd. At 19, Fairley came out as gay and, more shocking to both her and her family, pregnant.

Doctors started her on painkillers after complications giving birth to her son, and Fairley liked how “sociable” she felt when taking them. Since the pills were pricey, she turned to heroin and, later, meth. She’d been in legal trouble as a young teen—for swiping more than $400 from Walmart, a misdemeanor, while cashiering—but the drug use compounded her problems. Her older sister, Kai, told me that when Fairley was clean, she was “brighter, more alive.” In 2006, Fairley was convicted of a felony, for stealing more than $400 worth of gift cards while working at Macy’s. For a while, she and her son stayed at a girlfriend’s place and then a homeless shelter. In 2009, they landed a unit back in Potrero’s public housing, but the stability didn’t solve her problems. After her daughter’s birth, in 2010, Child Protective Services took both of her children because of her alleged drug use. Within a year, after she got clean and started trekking daily to a methadone clinic, she got her kids back.

Her son was arrested as a teen and went to live in a group home, Fairley said, but she dreamed of her daughter having a “normal” life—with “no kind of abuse whatsoever,” she said. Fairley kept her home from sleepovers and escorted her to the park and corner store. When her daughter started kindergarten, in 2016, her teacher, Chloe Dietkus, noted that the girl was always dressed sharply and, with her silly bravado, easily made friends. “At the end of the day she’d always run over to her mom,” Dietkus said, and they’d walk home, “seeming happy.”

Yet around that time, Fairley relapsed on drugs, and the deliveries that were dropped daily on her neighbors’ porches caught her attention. At that point, she didn’t know about the cameras or Nextdoor. In the months that followed, the police would find a cache of the neighbors’ belongings and mail in her possession. Her sister told me that Fairley generally sold the packages “for a little bit of nothing, just to get high,” or ate any deliveries that contained food. (Police say thieves generally sell their pickings on eBay, Craigslist, or to middlemen, who may hawk them at flea markets.) Fairley insisted to me that she stole only a small number of items—“I did it maybe once or twice, three times at the most; it wasn’t like a new job I went into”—and that she sold just one of them, a set of storage bins, for about $20. (She also told me she stole mostly in order to buy necessities, not drugs.) She thought the packages would be replaced by Amazon and other senders, so her gain wouldn’t be her neighbors’ loss. “That’s what eased my conscience taking someone’s property, because I’m not a bad person, it was just a bad choice,” she told me. “I was in a desperate state.”

As Fairley started hitting the stoops, her neighbors took to Nextdoor to discuss what to do. One group thought it was naive to expect a package to sit undisturbed for hours on a city stoop. Another camp felt the residents deserved the same rights to deliveries as in any other town. A third group was the solutions crowd: They advised having the boxes delivered to workplaces, or to Amazon Hub Locker, or with Amazon Key, a smart-lock system that allows couriers to drop packages directly inside a home or car. It turns out that while delivering packages is big business, so is thwarting their theft.

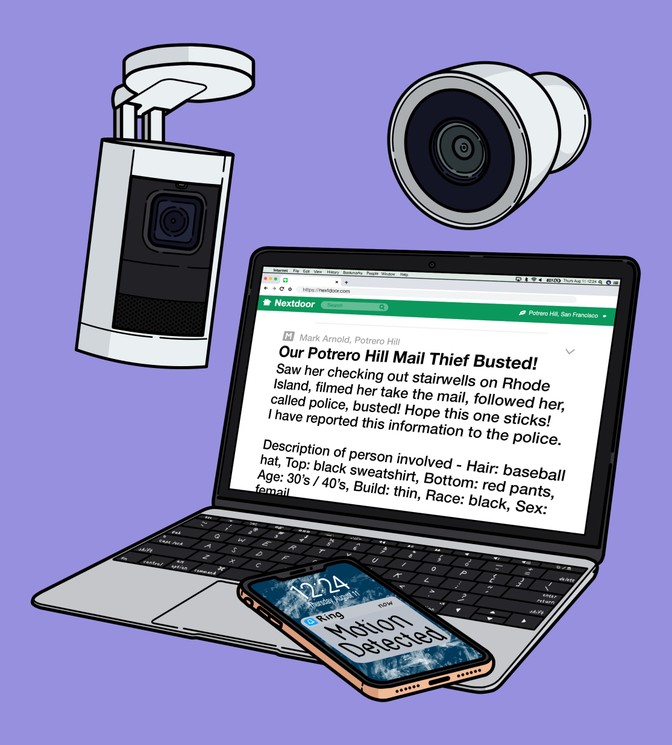

Perhaps a bigger threat to Amazon than the cost of replacing stolen goods is any hitch in its famously seamless service. In February 2018, Amazon acquired Ring, the smart doorbell and camera company. The official reason was to buoy neighborhood and home security, though much of that crime would be people swiping Amazon packages. (Nest, one of Ring’s main competitors, is owned by Google.)

Currently, 17 percent of American homeowners have a smart video surveillance device, and unit sales are expected to double by 2023. (Fairley was caught on Nest and another cam called Kuna, and several neighbors filmed her on their phones.) The popularity of these devices has led to the “porch pirate gotcha” film genre, a sort of America’s Funniest Home Videos of petty crime. In 2018, a 30-something white woman named Kelli Russell became viral international news for stealing boxes from 21 Dallas neighbors while looking like she was on her way to yoga class. “She’s blond and a former model, and it makes it explode,” her attorney Tim Menchu told me.

These videos, whether they go viral or not, often appear first on Facebook or Nextdoor. Nextdoor, a private company in San Francisco, was recently valued at $2.1 billion when it raised funds from top Silicon Valley investors. It relies on advertising for its revenue and has capitalized on its neighborhood-watch vibe by selling ads to home-security companies, including Ring (along with others such as ADT and SimpliSafe)—though Nextdoor CEO Sarah Friar told me home security doesn’t make up a huge proportion of their advertiser base, and only 5 percent of the site’s posts are in the crime and safety category. After press about rampant racial profiling on the platform in 2015, the company redesigned its app to prompt users who mention race to also include descriptors like hair, clothing, and shoes, which the company claimed reduced racial profiling by 75 percent.

Even so, Sierra Villaran, a San Francisco deputy public defender who handled Fairley’s case early on, has seen how social media’s rabble-rousing still leads to profiling of minorities and the poor. One of her clients, a Latino man, was arrested after a resident mistook him for someone recorded by their Ring device. (He was later released.) Not only does an arrest go on an innocent person’s record and potentially subject her to the use of force, Villaran said, it makes the accused feel like the cops will take the word of accusers, who are usually wealthier, over their own. Neighborhood surveillance and social media aren’t “adding quality to their life, making them any more safe.”

Back in Potrero Hill, a man mistook Fairley’s sister for Fairley herself, following her down the block and berating her as she passed out fliers. “He didn’t believe me,” said Kai, who was working for a community group at the time. “I was embarrassed, mostly.” She put her hand up in front of her face as he tried to take a photo of her. Friar, Nextdoor’s CEO, said that difficulty identifying people correctly is a human problem, not one Nextdoor invented, but the company has formed an anti-racial-profiling task force and continues to update the platform to encourage users to “get out of your bird brain—that immediate response—and into your cognitive brain, to pause and ultimately make a better decision.”

The proliferation of porch cameras surely contributes to the surveillance culture on Nextdoor and other social apps. Amazon’s Ring division has been particularly aggressive in marketing its products, including through city officials. Under the reasoning that more surveillance improves public safety, over 500 police departments—including in Houston and a stretch of Los Angeles suburbs—have partnered with Ring. Many departments advertise rebates for Ring devices on government social-media channels, sometimes offering up to $125. Ring matches the rebate up to $50.

Dave Maass, a senior investigative researcher at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit focused on digital civil liberties, said it’s unseemly to use taxpayer money to subsidize the build-out of citizen surveillance. Amazon and other moneyed tech companies competing for market share are “enlisting law enforcement to be their sales force, to have the cops give it their imprimatur of credibility,” said Maass, a claim echoed in an open letter to government agencies from more than 30 civil-rights organizations this fall and a petition asking Congress to investigate the Ring partnerships. (Ring disputes this characterization.)

Ring maintains that offering the discount makes the device more affordable, but Maass countered that, even with tax-subsidized rebates, “things like doorbell cameras are not a purchase someone would make if they already have trouble putting food on the table.” The cheapest doorbell costs $99, before rebates; the ability to store or review footage after the fact runs another $30 to $100 a year. “Does that mean that police are protecting the property of affluent communities more than the property of poor communities?” Maas asked.

In some cities, the relationship between the police and companies has gone beyond marketing. Amazon is helping police departments run “bait box” operations, in which police place decoy boxes on porches—often with GPS trackers inside—to capture anyone who tries to steal them. Gearing up for one such operation in December 2018, police in Jersey City, New Jersey, exchanged emails, which I obtained through a public-records request, with loss-prevention employees from Amazon and a public-relations staffer from its Ring division. Amazon sent police free branded boxes, and even heat maps of areas where the company’s customers suffer the most thefts. Ring donated doorbells that police officers installed on their own stoops to film thieves, and offered to coordinate a PR campaign. At one point, the police department asked Ring if it could extend a discount on Ring devices to all police staff, and Ring obliged, offering $50 off.

After receiving news about the Jersey City sting’s early success—seven arrests in three days during a soft launch, and a segment on Good Morning America—Amazon’s Rob Gibson, then a senior program manager for loss prevention, wrote in a December 13 email to the department, “Insane how it took off! How many arrests now? You can bet on it that I am coming out at some point to buy you a beer. You have helped me more than you know here internally. I need a patch and any swag you have so I can rep the PD here in Seattle.”

During the sting, Ring introduced the Jersey City police to another program it offers: Police departments can join a Ring app called Neighbors, on which residents (mostly Ring owners) broadcast their footage to people nearby. If police want to solicit a user’s footage for an active investigation, Ring will send the user an email with the police request; if the user volunteers to cooperate, the footage is sent back to the police, along with the user’s name, address, and email. As part of the pitch to join, Ring offered the Jersey City Police Department a free Ring device for every 20 residents who downloaded the app.

Meanwhile, Nextdoor allows police departments to join the app to post neighborhood-level news and polls. For its part, Nest doesn’t actively partner with police, but it does answer subpoenas: It received more than 100 requests from governments and courts last year, and provided user data in about 25 percent of the cases. The tech also encourages people to act like police: Captain Una Bailey of the San Francisco Police Department told me about a case in which a resident had a picture of a burglar from a Nest Cam, and digitally tracked a stolen laptop to a homeless person’s tent—then called the police to make an arrest. “They had taken all these steps that basically hand us an arrest on a silver platter with all the evidence,” said Bailey. “I’m definitely an advocate of people installing cameras.” (San Francisco’s police department hasn’t participated in surveillance-device subsidies, the Neighbors app, or bait-box operations, but has joined Nextdoor.)

Stings and porch-pirate footage attract media attention—but what comes next for the thieves rarely gets the same limelight. Often, perpetrators face punishments whose scale might surprise the amateur smart-cam detectives and Nextdoor sleuths who help nail them. In Jersey City, the bait-box operation netted 16 arrests in 10 days. Offenders may be routed to drug treatment and housing, according to police emails to Amazon; those with previous convictions could be eligible for jail time.

In December, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas announced an enforcement campaign called Operation Porch Pirate. Two suspects were arrested and charged with federal mail theft. One pleaded guilty to stealing $170.42 worth of goods, including camouflage crew socks and a Call of Duty video game from Amazon, and was sentenced to 14 months of probation. Another pleaded guilty to possession of stolen mail—four packages, two from Amazon—and awaits sentencing of up to five years in prison and a $250,000 fine. Russell, the blond woman in Dallas, ended up on two years of probation. The California legislature is considering a bill that would elevate porch piracy to a burglary charge; it would be a misdemeanor or a felony based, in part, on the suspect’s criminal history.

While porch cams have been used to investigate cases as serious as homicides, the surveillance and neighborhood social networking typically make a particular type of crime especially visible: those lower-level ones happening out in public, committed by the poorest. Despite the much higher cost of white-collar crime, it seems to cause less societal hand-wringing than what might be caught on a Ring camera, said W. David Ball, a professor at Santa Clara University School of Law. “Did people really feel that crime was ‘out of control’ after Theranos?” he said. “People lost hundreds of millions of dollars. You would have to break into every single car in San Francisco for the next ten years to amount to the amount stolen under Theranos.”

That perspective was little comfort to San Franciscans in late 2017, when the city was the nation’s leader in property crime. In Potrero, Fairley had been captured on camera enough times, snatching packages or walking down the street with bundles of mail, that many in the neighborhood had a face and a name to attach to their generalized anger about ongoing nuisances. Fairley was correct in thinking that, in many cases, Amazon will replace pilfered packages. Her major miscalculation was in thinking that her neighbors would, therefore, just shrug and move on.

In December 2017, Mark Arnold, the senior vice president of marketing for a radiosurgery start-up, was working from home when he glanced out at his stoop and snapped into high alert: Ganave goddamn Fairley! He cut off a conference call without explanation and sprinted outside in his socks, cuing up his cellphone camera. Arnold had been keeping an eye out for Fairley all fall, since $691 of Walgreens, Target, and Burlington Stores charges showed up on a Chase card that had been mailed to him and that police had plucked out of Fairley’s backpack.

As he starts filming, Arnold confronts Fairley in a neighbor’s stairwell, holding some sort of paper. “So what’s going on?” Arnold asks, authoritatively. “We’ve got plenty of photos and videos of you stealing things up and down this street.”

“You don’t have me stealing nothing,” Fairley snipes back. He asks if her name is Ganave. She says it’s Jessica. “I pass out flyers every day over here,” she insists—from Nextel (which closed years earlier)—and adds, “Just because I’m African American don’t mean I can’t pass out flyers!”

“This has zero to do with race,” Arnold interjects. Fairley shoots back that it does. (Arnold is white.) Then she threatens him with a harassment suit, and he says he’ll be forwarding the tape to the district attorney. Fairley tells him that, when he does, he should include a note of clarification: “I didn’t see her doing nothing, but I’m assuming.”

After the spat, Arnold followed Fairley down the street, watching her take other mail—“fearless,” as Arnold would later describe her to me—and called the cops. He snapped a photo of Fairley for a forthcoming Nextdoor report as the police came and detained her. Neighbors thanked and high-fived him as he walked home, in socks, victorious—at least for the hour.

Arnold is a fit 51-year-old dad, with an aggressive likeability befitting his marketing job. He bought the flat he’d been living in a decade ago, when Potrero home values were half what they are today. (“I don’t consider myself wealthy by any stretch,” he said—which, in a city that reportedly has the world’s highest density of billionaires, isn’t entirely unreasonable.) At the time, he and Fairley lived within two blocks of each other, and both fell into a zone where students score poorly on tests and are given special priority in the school lottery. Fairley doesn’t drive, and she sent her daughter to the school they could walk to. Arnold sent his child to a higher-performing one farther away. Arnold didn’t know many of his neighbors, but he had been bonding with their online avatars on Nextdoor about their shared headache.

Arnold began combining the neighbors’ Fairley-related posts in a single document. They started with the first dispatch, from May 2017, with Margett photographing Fairley and her daughter. In October of that year, a friend of Arnold’s, then a VP at Flipboard, followed Fairley in his Prius, watching her go door to door collecting packages—a mail carrier in reverse. In November, a cam caught a lithe woman who looked like Fairley crawling up a home’s steps to seize a fat Amazon pouch of lug nuts, a rosary dangling from her neck. Two weeks later, neighbors were gardening on a shared strip of land when Fairley passed by balancing a long lamp box on her shoulder. (Fairley claimed that the box contained her own headboard and lampshade.) Seeing an address written in big letters for a home in the opposite direction, one of them grabbed the box and demanded to see an ID to prove Fairley lived there. A second man called 911 as a woman videoed Fairley’s ensuing tirade: “That’s why people get shot. You don’t pull somebody’s package off their fucking arm,” Fairley snapped, then stalked off.

Two incidents—the Googler and the bus; the Prius calling in Fairley—resulted in charges (petty theft, mail theft, receiving stolen property, and possession of heroin—all misdemeanors), and tickets for court dates. But Fairley regularly skipped her hearings—she’d lose track of the dates, she later told me, and just had “a lot going on”—which slowed the process of resolving the cases. Again and again, in her absence, the judge would issue bench warrants, and Fairley would eventually be arrested and booked into jail, from which the judge would release her to await her next hearing, with demands that she report to diversion programs or Narcotics Anonymous meetings—all while neighbors continued to report on Nextdoor that they were watching her steal mail.

San Francisco County courts have long referred many low-level offenders to rehabilitative programs while they are awaiting trial rather than have them sit in jail. This practice endlessly angers the victims of the property crimes, and concerns cops, too. “Our big request is for consequences,” said Commander Raj Vaswani, who headed the district responsible for Potrero at the time, adding that police typically only pursue an arrest if a person or a camera directly witnesses the package being stolen.

Yet locking up low-level criminals won’t solve what Ball, the Santa Clara University law professor, believes is the root cause of these crimes: poverty within astronomically expensive cities. “Everyone assumes that jail works to deter people. But I don’t know if I were hungry, and had no other way of eating, that that would deter me from stealing,” he said.

Arnold thought the whole cycle looked like institutional apathy. Three times, he walked up to the window at Vaswani’s station in the Bayview, the southeastern-most district of San Francisco, which is among the poorest, with high violent crime rates. The officers seemed underwhelmed by his package gripes, saying that petty theft is a cite-and-release sort of misdemeanor and asking, “What do you want us to do?” Arnold would respond, “Prosecute her,” referring to Fairley. They said that was the district attorney’s job.

Vaswani acknowledged that his station was responding to two different sets of resident concerns: “Violent crime might be targeted, and doesn’t affect the average person walking their dog every morning.” He defended his station’s response to the package theft, saying he dispatched a bicycle officer to cut down on that kind of quality-of-life crime, which isn’t seen as serious “but, to the average person that lives there and pays really high rent, or has bought a really expensive house in a really nice neighborhood such as Potrero Hill, … affects their daily lives.”

In January 2018, Arnold took time off from work to attend one of Fairley’s hearings, at the suggestion of the prosecutor then handling the case. (An organized group of San Franciscans also has taken to sitting in on burglary cases to show elected judges that voters are watching.) While Arnold sat in the courtroom, his wife texted that Fairley wouldn’t be showing up: She was on their stoop that very moment, apparently in the middle of another stealing expedition. (Fairley was not charged in this alleged incident, and her lawyer declined to comment.)

Margett had retaliated against Fairley by placing her Boston terrier’s poop in a decoy box on her stoop. (Someone picked it up; Margett doesn’t know who.) Arnold watched a vigilante method online: having a blank shotgun shell go off when someone lifts a decoy box. He feared that the startled thief could fall down his stairs and sue him, and concluded that it wouldn’t “end well.” He headed back to Nextdoor, reporting that going to court had been a fiasco but that the judge had issued warrants for Fairley’s arrest. He recommended that neighbors call 911 as soon as they saw her, and that they “gather watertight evidence for the next trial.”

Word about Fairley had gotten back to her neighbors in public housing—at least to Uzuri Pease-Greene, who runs a nonprofit community center out of her building and serves as a safety liaison to the police. Pease-Greene was one of the few residents of that part of the hill active on Nextdoor back in 2014, and soon realized that she had stumbled into “an upper-middle-class Facebook,” on which the house-dwelling folks blamed people who lived in public housing for every woe. “They stepped on a banana peel,” she said, “and would be like, ‘The projects put it there!’”

On Nextdoor, Pease-Greene, a black woman, blasted stereotyping while making it clear that she didn’t condone any shenanigans, no matter who the perpetrator was. In a city with staggering racial disparities in its criminal-justice system—African Americans make up only about 6 percent of the population but more than half the county jail inmates—Pease-Greene was privately relieved that the city’s thieves, including those outed on Nextdoor, were of all races. “It’s sad that I have to think like that, but it’s like, oh God, thank you!” she said. “This is everybody doing it.”

Most comments about Fairley weren’t explicitly about her race, which isn’t to say that they were gracious. Pease-Greene read some of the men’s threats toward Fairley—which ranged from “Might as well taze her next time she’s caught. Preferably put her in a coma” to wishes of “an extremely swift kick in her saggy pants a$$”—and worried that the writers might not be kidding. “When you get people that are talking like that, who have white privilege, they’re not going to do any jail time,” she said. Pease-Greene told an assistant district attorney she knew that the clash was getting out of control, and she warned Fairley that footage of her taking packages was all over Nextdoor.

While Fairley didn’t stop, and neighbors on Nextdoor vented that no one cared about their complaints, authorities were, in fact, circling in. They started exacting collateral with a much higher price than anything Fairley took.

Fairley’s troubles started ramping up one night in November 2017, when police spotted her in the Potrero projects and arrested her on bench warrants. They added a child endangerment charge when the officers dispatched to Fairley’s unit found that her daughter had wandered outside, alone and upset. (The charge was later dropped.) Fairley had no one to call to take her daughter, and the cops contacted Child Protective Services, which eventually had her stay with a paternal great-aunt.

Fairley cycled in and out of jail in the following months. She said that with her daughter gone, she sometimes stopped getting her government cash assistance, exacerbating the poverty that had initially led her to steal mail. (She did, at points, still get food stamps.) Fairley said her immediate need for money made it impossible to launch a job hunt. “I live now, today. I have to eat tonight.” At one point, Arnold thought he spotted her stealing produce at Whole Foods; he reported it to a manager, but Fairley wasn’t charged. When told about this, Fairley’s defense attorney, Brandon M. Banks, described Arnold as “the ring leader in the smear campaign” against his client. “It is unfortunate that he believed every time he saw Ms. Fairley at the grocery store or with a package in her hand he believed she was stealing it.” Arnold, however, argued that the evidence of Fairley’s thefts was “irrefutable.” “It’s not a smear nor an opinion, just an unfortunate reality,” he said. “It’s very disappointing [that] Banks has chosen to smear the victims.” Kai told me that when she brought up stealing with her sister, Fairley would say that “she has to do what she has to do, and someone else is going to take it if she doesn’t.”

In January 2018, yet another neighbor grabbed a package out of Fairley’s hand, and signed a citizen’s arrest form, leading to another charge of petty theft. In February, a judge slammed Fairley with a stay-away order for blocks where she’d been accused of stealing. In March, the police and U.S. Postal Service inspectors rustled through Fairley’s unit with a search warrant, finding clothes and other items she had been seen wearing in cellphone and porch-cam footage, along with mail and documents printed with the names of 40 different neighbors. After missing yet more court dates that spring—resulting in more warrants, more arrests—she was jailed again in April, and released the next month with an ankle monitor.

Fairley’s time was up. Her landlord had issued warnings because of the police visits to her unit, she told me. Fairley said that in June, she found a “notice to vacate” on her door. Before she could challenge it, sheriff’s deputies strode into her unit with an arrest warrant—she’d missed another court date—and found her hiding under a gigantic blue teddy bear. This time, the judge didn’t let her out of jail, and Fairley couldn’t pay bail as the prosecutor pursued charges for the three alleged stealing episodes. Banks stepped in from San Francisco’s aggressive public defender’s office. Fairley rejected a plea bargain that Banks considered a “terrible” deal (including a stay-away order from Fairley’s surrounding neighborhood and, to his thinking, too much jail time)—and the case of Ganave Fairley v. Neighbors of Potrero Hill hurtled toward trial.

In August 2018, Fairley plunked herself behind the defense table for a four-day blur of disputes over Nick’s solar panel battery switch, Daniel’s Apple keyboard, Alexandra’s HelloFresh groceries, Sorcha’s Montessori books, Micaela’s and Elizabeth’s checks, Samantha’s dog’s probiotics, Jennifer’s, Jabari’s, and Brigette’s United credit cards, and, by God, Dell’s hot sauce—representing a total of 23 misdemeanor charges of “petty theft,” “receiving stolen property,” and “mail theft,” plus the drug possession charge for the heroin found in Fairley’s pocket back in August 2016 when this had all started.

The prosecutor, Jennifer Huber, told jurors that the case was “not a whodunit: The defendant was caught red-handed stealing, over and over and over again.” Fifteen neighbors testified, and the prosecutor showed jurors the evidence they’d collected: The photo of Fairley’s daughter sticking her tongue out at Julie Margett. The cellphone video of Fairley sniping “That’s why people get shot” after the gardening neighbor took the lamp box from her. The spat where she’d called Arnold a racist. None of these incidents were charged as crimes but were admitted as evidence of Fairley’s m.o., though Banks, the defense attorney, alleged that the parade of squabbles was just to sully her character.

As Banks saw it, Fairley had been caught in a web of surveillance, gentrification, and racism, in which vigilante neighbors targeted her for anything that went missing, when, in fact, many other porch pirates were also stealing in Potrero. She might have stolen some items, but not everything she was being blamed for taking. “This case is about mob mentality and the lowest-hanging fruit,” Banks declared in his opening statement. “And the lowest-hanging fruit in this case is Ms. Fairley.”

He emphasized that she was a longtime resident of Potrero, a neighborhood whose rising wealth had alienated her from her own community. (To be fair, while some of the neighbors were relative newcomers, several victims testified that they’d lived in Potrero for decades.) Given that Fairley had been caught on tape stealing several packages, and cops had recovered other items in her possession, some of Banks’s case seemed to rest heavily on the “guilty beyond a reasonable doubt” standard, focusing on the fact that several of the victims, such as the man who had lost his subscription hot sauce, had never seen Fairley taking the stolen items:

“Well, I guess, when did you first become aware that this hot sauce was missing?”

“It’s hard to tell. I get them every month. So I don’t know.”

“You don’t know who took the hot sauce?”

“I don’t know who took it. Just, I recognize this”—the sauce found on Fairley—“is definitely my hot sauce.”

(It was.)

Fairley told me that she was surprised by how angry the neighbors seemed. In court, she wore a suit Banks had brought her from his office’s wardrobe, and Arnold noticed that she had filled out in jail. “She looked groomed, slept, and fed,” Arnold told me later. “It made me believe she was being properly looked after.” When Arnold took the stand, Banks tried to get him to admit that he’d badly wanted to get Fairley arrested. “Do you normally post telling people that they should call 911 irrespective of whether they see someone commit a crime or not?”

“I do not, normally. This is a very abnormal situation.”

Arnold’s credibility went mostly unscathed. Even so, Banks did succeed in showing who gets the benefit of the doubt in Potrero. He asked the gardening man who demanded identification from Fairley in the lamp box episode whether he would investigate everyone walking down the street with a package. His answer teetered on profiling: “If they look suspicious, and it’s not their address” on the delivery. When Banks then dug in to ask whether he thought Fairley was wearing something suspicious, the man said, “She just had a hoodie, and she was carrying a box from the next block down. I’ve never seen her in that block, and I know a lot of people who live down there, so I assumed it wasn’t her box.”

While wealth and race disparities were obvious in the courtroom, they weren’t on trial. Nor was the citizen surveillance facilitated by porch cams and Nextdoor to the benefit of corporations and venture capitalists. Nor were such lofty systemic issues as the criminalization of poverty and addiction. The question was simply: Did 12 jurors think Fairley once had heroin in her possession and had stolen some items? (Mid-trial, the prosecutor reduced the 24 counts to 16, of drug possession, theft, and receiving stolen property.)

After a day of deliberations, the jury returned a packet of verdict sheets on which one of them had scrawled “GUILTY,” determining that Fairley had committed every act she was charged with. They even convicted her of stealing when they had been given the alternative of finding that she merely possessed stolen items.

In sum: She was found guilty of the drug charge, of five counts of receiving stolen property (one was later thrown out), and of every single theft.

The case continues to be litigated, both in and out of the courtroom. Her lawyer filed an appeal, which is ongoing as of this writing, arguing that each stealing spree should have constituted a single conviction, rather than each stolen item. And in Potrero, Fairley and the neighbors weren’t done with each other yet.

Ahead of Fairley’s sentencing hearings in August and September, four neighbors submitted victim statements to detail the toll the crimes had taken. Read aloud in the courtroom by the prosecutor, Arnold’s topped them all: He’d written that his home “no longer feels sacred,” adding that Fairley’s remark about people getting shot made him fear retribution. He had no choice, he’d written, but to move out of the city. Fairley thought he was exaggerating, to force her out of the neighborhood instead.

Judge Charles Crompton acknowledged that economic necessity had contributed to Fairley’s actions, and sentenced her to a minimum of one year in a full-time drug rehab program—the first stage of three years of probation—and imposed a stay-away order from the blocks she’d targeted. Fairley, having been kicked out of her Potrero unit while in jail and pushed into the city’s growing ranks of homeless people, was heartened by the news of the residential program. At least it would be a roof over her head.

Yet during her first week at the rehab program, in mid-October, Fairley learned that having taken other people’s stuff meant that she had lost all of hers; everything in her unit had been thrown out because she hadn’t been around to claim her possessions. Losing photo albums with her children’s pictures in them hurt the worst: “No memories, nothing,” she told me. Since she was no longer a resident of Potrero’s public housing, she had also lost her chance to move into the incoming redeveloped complex. Then, within a month of arriving at the rehab program, she failed three drug tests—meth, she said—and was kicked out.

At the time, her sister, Kai, was squatting in a Potrero public housing unit, and says Fairley initially stayed with her, telling Kai that she hadn’t expected to “come home to nothing.” Then Fairley climbed through a window into her old, now-empty unit in Potrero and began sleeping there on cushions she had scavenged. She didn’t call her daughter on Halloween or Christmas; the girl told the great-aunt who’d taken her in that her mom was “lost.” When Fairley was a no-show for a December 26 probation hearing, the judge once again called for her arrest.

She wasn’t lost for long. Back in Potrero, Julie Margett opened her door late one night in December to her union-leader neighbor, Jason Rosenbury, who was bringing her some homemade cooked collard greens. He told her that someone was sleeping on top of the clothes she had put on her bench for people to take. The sleeping woman heard him, rustled, and said to Margett, in a friendly tone, “I know you from court!”

Margett was stunned. “Are you Ganave?” Fairley said she was. With no apparent rancor toward the woman who’d first put her on Nextdoor, Fairley told Margett she’d gained a lot of weight in jail and had stopped stealing. She added that she’d lost everything and had nowhere to go. Margett told her she couldn’t sleep on the bench, but suggested a women’s shelter in a nearby neighborhood and gave her a jacket, along with some sparkling water and chips. Fairley said she’d move to a bench up the street and ambled off.

On New Year’s Day, a new post entitled “A bold daytime porch thief” appeared on Potrero’s Nextdoor. A software engineer at Square had posted a Nest Cam video of a woman jauntily striding up to his entryway and checking inside a utility box where postal workers leave deliveries, a package already tucked under her arm. Margett dove into the comments:

“OMG—I think that’s Ganave Fairley?”

Mark Arnold wrote that it was her—noting her inward-jutting left knee—and urged people to call 911 if they spotted her doing anything illegal, including stepping foot in the stay-away zone.

Uzuri Pease-Greene, Nextdoor’s unofficial public housing spokeswoman, had been rooting for Fairley. She saw the new post, too, and thought, Son of a bitch.

Squatting in her unit and having lost her daughter and her belongings, Fairley was apparently back to what had gotten her into this mess in the first place. A month later, in a new Nest video shot at the same entryway, Fairley was seen mumbling to herself, tripping on a recycling bin on her way down the sidewalk. (Fairley told me she wasn’t interested in talking about the videos.) Ten days later, cops found her in her former unit and hauled her back to jail on warrants.

I visited Fairley in jail several times this past spring while she was waiting for another rehab program to accept her. As she talked about the events that had gotten her there, she was lucid and friendly; while she still grew irked when talking about her neighbors, she showed scant traces of the woman spewing bile in the videos. I asked her whether she had found landing back behind bars to be—

“Relieving?” Fairley interjected. “Yes.”

Fairley continued to insist to me that she only stole a couple of times, and she seemed to feel worse for herself than for the people she stole from: “I never took anything that was somebody’s worldly possessions or anything that was personal … I didn’t feel like it was that big to them.” Still, as of last spring, Fairley knew the onus was now on her to right her life: If she failed a second rehab program, the judge could make her serve her year-long sentence in jail, diminishing her chances of ever getting her daughter back. This time, she felt “a bit more urgency” than when she was sent to the first program in the fall of 2018. When I told Arnold about Fairley losing her daughter, housing, and possessions, he said, “You gotta have empathy, that sucks to be in that position, but hopefully the city is throwing a lot of resources at her, hopefully she takes advantage of it.”

In late spring, Fairley’s childhood history seemed to repeat itself: A judge granted permanent guardianship of her daughter to the girl’s great-aunt in the city, Mary Jane Boddie-Cobb, a 59-year-old woman who works at the Department of Veterans Affairs. Over the last year, the 8-year-old has gotten a tutor at her new school to get up to grade level, and Boddie-Cobb has been trying to help her break bad habits, like taking things in the house that aren’t hers and claiming that she “found” them. Boddie-Cobb hopes the girl can return to Fairley, or even her nephew—the girl’s father—if they get themselves together, but now that nearly two years have passed since Fairley first lost custody, the bar is higher: She must proactively petition the court that it’s in her daughter’s best interest to live with her and prove that there’s a problem with the current placement.

That will require having a home, so Fairley told me she applied for the public housing wait lists in San Francisco and nearby counties. It also requires that she be drug free. In May, she showed up in San Francisco court, where Judge Crompton sentenced her to a year in a Salvation Army recovery program while on probation.

From his bench, Crompton (again) looked at Fairley (again) hunched over the defense’s table in her orange jail sweats.

“This is an important day,” he said.

“Right,” she replied.

Crompton told her that, while he could give her more jail time if she failed the program, his dream was for her to get clean and get her daughter back. “I know that you can do these things,” he told her. “I want to see you succeed.”

“Thank you,” Fairley said. Later that afternoon, she walked out of county jail again—this time, to a rehab facility in a nearby colonnaded building just three blocks away, to try to prove that history wasn’t fate, and that she could change.

Even with Fairley gone from Potrero, the porch piracy has continued. Last spring, Mark Arnold ordered a $24.38 multipack of Sloppy Joe sauce on Amazon for an 1980s-themed Stranger Things premiere party. (Despite writing to the judge that he had no choice but to move, Arnold still lives in the same flat.) He forgot to change the delivery address to his office—where he has everything sent these days—and it was taken before he could pick it off his stoop. Arnold thought about reporting to Amazon that the kit had been stolen, but decided to just order another set. The thought of moving to a more bucolic locale was certainly appealing, he told me; the city’s property crime remains high, and lately, he said, he’s been looking into his options to get out. Even so, he didn’t want to uproot his daughter. “That’s what’s made me such a pain in the ass,” he said, referring to his neighborhood-watch habit.

Potrero’s conflict with Fairley herself is not over. Sometime in late summer, Fairley left her Salvation Army program early. She skipped a probation status hearing, and the judge issued new warrants for her arrest. Around that time, Uzuri Pease-Greene spotted Fairley walking through Potrero’s public housing. If she was planning to squat in her old unit again, that wouldn’t be an option for long: The block’s residents were moved earlier in the summer into their new homes in the redevelopment plan, and the now-vacant buildings are set to be demolished later this year. Mary Jane Boddie-Cobb told me that Fairley’s daughter no longer asks as much about her mom.

Starting in mid-September, posts started popping up on the Neighbors app showing Ring videos of someone—Fairley, it was clear to me—hitting Potrero stoops. In one, she wrestles with something on the ground before someone off-camera yells, “Get the fuck out of here, man!” (A commenter wrote, “So satisfying. Jump him next time!”) Another video includes a close-up of Fairley’s face as she grabs at something offscreen while wearing a Rastafarian hoodie; in an accompanying post, the user explains that a package had been ripped open but left in place. (Fairley couldn’t be reached to comment on the videos; Banks declined to comment.)

This fall, Mark Arnold’s wife was trekking home from a Potrero bus stop with their daughter when she spotted what looked like a familiar figure in a baseball cap, with a warped left knee, a few blocks from where Fairley used to walk home from school with her own daughter. The woman wasn’t carrying any mail, or going up anybody’s steps, so Arnold’s wife didn’t call the cops—nor did she take any photos, or post on Nextdoor.

But she did turn back for a last glimpse—surprised, after all, to see her back in the neighborhood, after everything that had happened. The woman in the baseball cap continued to stroll up the street: alone, gazing up at homes, as if searching for something lost.

This article is part of our project “The Presence of Justice,” which is supported by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge.