Nicolas Roeg's arthouse classic The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) stars Bowie as an alien in disguise (Credit: BFI)

One of the many pioneering elements of David Bowie's career was his commitment to the visual. For Bowie, sound and vision went hand in hand. His many star personas – Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, Major Tom – each came with their own fully realised aesthetic worlds, costumes, make-up and artwork that were as instantly recognisable as the music itself. Long before the advent of MTV, Bowie was making short films to promote his music, and he would go on to push the boundaries of the form with iconic videos such as Ashes to Ashes. Indeed, Bowie's final gift to the world came in filmic form – the video for his last single Lazarus was released on 7 January 2016, just three days before his death.

It's unsurprising that this most mercurial of artists, with his visual sensibility and many alter-egos, would be drawn to film. Yet, while Bowie's legendary status in music is beyond question, quantifying his contribution to cinema as an actor is more complicated. In the three decades between The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and The Prestige (2006), Bowie appeared in dozens of films but – despite that span of credits – only a few of these roles came close to making the most of his talent. When we leave aside the many cameos – of which the uncontested crème de le crème is Bowie solemnly adjudicating a runway walk-off in Zoolander – and the forgettable flops – the less said about Just a Gigolo, the better – we are left with only a handful of performances. Yet those acting roles that did manage to effectively exploit Bowie's gifts are easily enough to secure his status as a cinema icon. When matched with an inventive director, Bowie could be an unforgettable screen presence.

The star's charismatic performance as the Goblin King in the 1986 fantasy Labyrinth has helped make the film a cult classic (Credit: BFI)

From the start of his career, Bowie was an artist who often turned to cinema for inspiration. Whether referencing Stanley Kubrick on Space Oddity, posing like Greta Garbo on the cover of Hunky Dory or channelling German expressionism as the Thin White Duke, Bowie was constantly drawing on film iconography in his music. Filmmakers quickly identified his potential as a subject, with documentaries such as DA Pennebaker's Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1979) and Alan Yentob's Cracked Actor (1975) capturing spectacular live performances and intimate behind-the-scenes footage.

Cracked Actor depicts Bowie at the height of his 1970s fame, rattled by cocaine, and driven to the brink of sanity by the pressures of stardom. It was this image of a strung-out Bowie driving around LA in the back of a limousine that inspired Nicolas Roeg to cast the musician in his first major film role. The Man Who Fell to Earth is the story of Thomas Newton, an alien on a rescue mission from his home planet who crash-lands on Earth and ends up stranded in the New Mexico desert. Disguised as a human, Newton attempts to raise money for a new spaceship by selling alien technologies but soon becomes corrupted by human vices.

Without Bowie, The Man Who Fell to Earth would be an intriguing curio; with him, it becomes a classic.

By 1975, Roeg had already established his reputation with arthouse landmarks such as Walkabout and Don't Look Now. The Man Who Fell to Earth brought together one of the most interesting directors of the 1970s with the decade's defining popstar, and the result is a trippy triumph. Like Bowie's music, the film mashes up genres – sci-fi, political thriller, romance – and channels the counter-cultural mood of the time to create something bracingly new. With a fragmented, often confusing narrative, it's a genuinely risky film that feels as if it could crash land at any moment, but which is held together by a magnetic central performance. Without Bowie, The Man Who Fell to Earth would be an intriguing curio; with him, it becomes a classic.

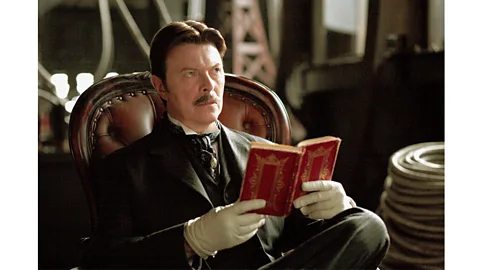

Christopher Nolan's period thriller The Prestige (2006) features Bowie as maverick inventor Nikola Tesla (Credit: BFI)

Part of Bowie's power lies in his astonishing physical presence. Pale and emaciated, with streaks of red hair falling into mismatched eyes, Bowie requires little make-up to convince as an alien in disguise. A series of retro costumes – wide fedoras, loose high-waisted trousers, tight white T-shirts – draw out his androgynous beauty and emphasise Newton's genderless nature. That blurring of gender boundaries is reflected too in Bowie's frail physicality and delicate movements. Bowie's Newton moves initially with the faltering steps of someone learning to walk again. When he collapses in a hotel lift, chambermaid and future lover Cindy Lou (Candy Clarke) scoops him into her arms, and carries him to bed as if he weighs nothing at all.

But there is more to this performance than a dazzling surface. In the throes of his addiction, Bowie was in a fragile mental state during the shoot, and his sense of dissociation is perhaps part of what makes him so frighteningly credible as a stranded alien. At times, as Bowie oscillates between sweet helplessness and terrifying volatility, it feels more like a possession than a performance. Scenes in which Newton succumbs to addiction, sitting before a wall of wailing televisions or stirring his drinks with a gun, crackle with manic energy. The final image of Newton slumped in his seat, just another drunk with nowhere to go, is devastating.

By casting Bowie, Roeg encourages us to blur the boundaries between character and performer, and in doing so draws out new layers of meaning. Newton, adrift in cowboy country with a London accent and British papers, is an alien in several senses. It's possible to read the film as a straight sci-fi, but also as a metaphor for the outsider status of the immigrant, for the loneliness of genius or for the isolation of celebrity. Much of Bowie's art feels like it comes from another planet but, as his tender performance demonstrates, to be exceptional can be alienating.

In the biopic Basquiat (1996), Bowie plays the role of Andy Warhol with a wry playfulness (Credit: BFI)

In The Man Who Fell to Earth, Roeg set the template that would define Bowie's film career. All of his most successful screen performances share certain hallmarks – an unusually imaginative director, a role as an exceptional outsider, a blurring between star persona and character. Music critics tend to praise Bowie's chameleonic quality, his ability to switch from extra-terrestrial rock to blue-eyed soul to polished pop in the blink of an eye. Yet as an actor, Bowie was no chameleon – instead of disappearing into his roles, he floated above them, always a level removed. This distance meant that every part Bowie played was inevitably in conversation with his many alter egos, and with the nature of fame itself.

Reality and performance

Bowie's most effective performances tap into that meta-commentary. An example of this is his brief but memorable appearance as Andy Warhol in Julian Schnabel's biopic Basquiat (1996). Based on Schnabel's friendship with the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, the film is full of characters modelled on real people from the 1980s New York art scene. In real life, Warhol was a hero of Bowie's – there's a song dedicated to him on Hunky Dory – and the two had crossed paths at parties. By casting Bowie, Schnabel has one legendary artist disguise themselves as another, and in doing so taps into the same ideas about fame that defined Warhol's art. Bowie delivers a delightfully ironic turn, peering out from beneath a silver shock wig (taken from Warhol's real-life wig collection), his lip curled in constant amusement. In a film that sometimes takes itself too seriously, Bowie delivers a dose of wry camp, playfully exposing the shallow nature of artworld celebrity and once again blurring the boundaries between reality and performance.

On a similar wavelength, but even better, is Bowie's supporting role as the inventor Nikola Tesla in Christopher Nolan's tricksy period thriller The Prestige (2006) . Tesla was another famous maverick, a Serbian-born pioneer of electronic engineering who died in 1943 after a troubled but influential life. In Bowie's interpretation, Tesla becomes a kind of real-life twin to Thomas Newton, a displaced genius who teases the boundary between magic and science – and is ultimately destroyed by the greed of those who surround him. Like Newton, Bowie's Tesla arrives with a bang, appearing apparently from nowhere in a cloud of sparks. Bowie's occasionally extravagant performance – all lustrous moustache and lilting, indeterminate accent – is tempered by a core of vulnerability that grounds this archetypal mad scientist in poignant reality.

In Tony Scott's 1983 film The Hunger, Bowie put in an elegantly unhinged performance alongside Catherine Deneuve (Credit: Getty Images)

The same otherworldly quality that makes Bowie's takes on Warhol and Tesla so successful, is also used to beguiling effect in two 1980s cult classics. Jim Henson's fantasy Labyrinth (1986) was a commercial disappointment on first release but has since become a cult favourite. Bowie's justifiably much-loved performance as the Goblin King is key to the film's appeal. Resplendent in bejewelled blouses, outrageously tight trousers and a shocking wig that tops even Warhol's, Bowie relishes the opportunity to play the villain. On his own terms, Henson was himself something of a genius, and like Roeg he delivers a series of memorable images that capitalise on his star's incandescent charisma. Bowie's Jareth fizzes with mischievous magic, as he materialises like a shimmering apparition in an open window or strides upside-down across rotating Escher-indebted stairways.

Tony Scott's uneven The Hunger (1983) is less satisfying overall but does offer the tantalising prospect of Bowie as one half of a stylish vampire couple alongside Catherine Deneuve. The Hunger came out immediately after the release of Bowie's phenomenally successful Let’s Dance album, and the role offers a goth twist on his slickly handsome 80s pop persona. Bowie's creature of the night is exquisitely stylish and devastatingly sexy, prowling blue-lit Manhattan nightclubs in sunglasses searching for his next fix. The film is worth watching for Bowie's elegantly unhinged performance and for its moments of delirious excess, such as an exhilarating opening sequence in which Bowie and Deneuve procure a couple of hipsters for dinner to an unsettling Bauhaus soundtrack.

In the same year that Bowie went full goth in The Hunger, he also delivered one of his most substantial and grounded performances. In Nagisa Ōshima's Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence (1983), Bowie stars as Major Celliers, a soldier serving in Java during World War Two, who is captured and sent to a brutal Japanese prison camp. In confinement, Celliers becomes a leadership figure for his fellow prisoners and an object of obsession for the camp's commander Captain Yonoi (Ryuichi Sakamoto).

Bowie brought a subversive edge to his role as a soldier in a Japanese prison camp in 1983 film Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence (Credit: BFI)

In many ways, this is Bowie's straightest performance. Tanned and movie-star handsome, aside from his endearingly crooked British teeth, Bowie's Celliers initially embodies dignified masculine power. Yet, as is always the case with his best performances, Bowie brings to the surface a subversive subtext, drawing out the queerness that lies beneath many war-movie tropes. As the film progresses, Celliers infuriates his captors with increasingly transgressive acts of rebellion, showing his contempt for authority through flamboyant performances, singing songs, collecting flowers and even by kissing Yonoi. By casting Bowie alongside fellow musician Sakamoto (a legendary popstar in his own right), Ōshima presents us with a face-off between two titans of 20th-Century music. The homoerotic tension between the pair culminates in an ambiguous moment when, having sentenced Celliers to be buried alive, Yanoi visits the condemned man to cut a lock of his hair, like a fan or a lover would. The film's climactic image of Celliers buried neck-deep in the sand, his hair bleached by the blazing sun, is an arresting tableau fit for an album cover.

In the aftermath of the star's death, such indelible images have gained new significance. Bowie's death robbed us of future music, but it also took away the possibility of more film roles, of more opportunities for this most unusual of artists to enchant and surprise us at the cinema. Not all of Bowie's roles were worthy of his talent, but those that were have at least left us with some kind of compensation. The Starman may be gone, but some element of his extraordinary charisma will always remain, a glittering after-image burned forever on to the silver screen.