Exactly a year ago, Oxford University scientists launched a joint enterprise that is set to have a profound impact on the health of our planet. On 11 February, research teams led by Professor Andy Pollard and Professor Sarah Gilbert – both based at the Oxford Vaccine Centre – decided to combine their talents to develop and manufacture a vaccine that could protect people from the deadly new coronavirus that was beginning to spread across the world.

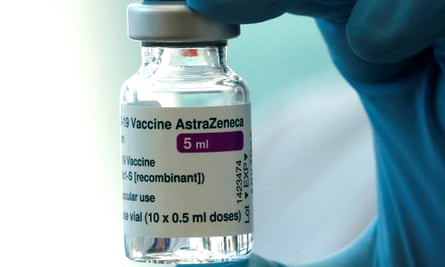

A year later that vaccine is being administered to millions across Britain and other nations and was last week given resounding backing by the World Health Organization. The head of the WHO’s department of immunisation, vaccines and biologicals, Professor Kate O’Brien, described the jab as “efficacious” and “an important vaccine for the world”.

It has been a remarkable journey for the Oxford Vaccine Group and in particular for its leaders, Gilbert and Pollard, who have worked tirelessly to create their cheap, easy-to-distribute vaccine and to defend it, patiently and politely, from attacks by pundits and politicians.

Some US observers have criticised protocols for the vaccine’s trials, while French president Emmanuel Macron recently claimed the Oxford vaccine was “quasi-ineffective” for people over 65. These claims were firmly debunked last week by the World Health Organization, which gave the vaccine its glowing recommendation. For good measure, the WHO also fell into line with the UK’s decision to delay second dose vaccinations to increase primary protection against the disease.

“I think we really need people to make positive statements about vaccines to build confidence. Negative comments pose the risk of undermining that confidence,” Pollard told the Observer last week.

In developing a Covid vaccine that is easy to transport and cheap to administer, the Oxford Group has again underlined the strength of UK science, which has already been bolstered by the country’s remarkable Recovery trial which last week revealed the efficacy of another lifesaving, anti-Covid drug: Tocilizumab.

In addition, Britain’s geneticists have been hailed for their efforts in detecting potentially dangerous new virus strains – by carrying out the lion’s share of virus variant sequencing across the planet.

Our politicians may have bungled national Covid strategies, but our scientists have performed confidently. This is, in part, a testament to the width of their experience as exemplified, at Oxford, by Gilbert who years earlier had set up her own vaccine research group and had already worked on trials of vaccines for Ebola and later for the recently emerged Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (Mers). Importantly, the latter is caused by a coronavirus, the same type of virus that is responsible for Covid-19.

“I learned how to design a vaccine, get it manufactured, get approvals for a clinical trial and get that clinical trial up and running,” Gilbert told the Observer last week.

Then, at the end of 2019, a novel, occasionally fatal respiratory illness appeared in Wuhan, the sprawling capital of central China’s Hubei province, and by early January was spreading outside China.

The Shanghai virologist Professor Zhang Yongzhen first decoded the virus’s genetic structure and published his results on the internet. Gilbert and her colleagues immediately began working on a vaccine using Zhang’s data.

However, it quickly become clear that the new outbreak was going to be something very much bigger than early cases had suggested and much larger trials of vaccines would be needed. So Gilbert sought the advice of Pollard, a paediatrician and expert on running large-scale vaccine trials. “Normally we work on our own projects,” said Pollard. “But we quickly realised this was something that needed a large team to tackle. So we brought our research groups together.”

At this point, the disease had not yet become the horror that we have seen since then, added Pollard. “However, it was soon obvious that we were about to have a huge global problem, one that would transform all of our lives for the rest of the time that we are going to be on this planet.”

To create their vaccine, the Oxford team took a common cold virus that infects chimpanzees and engineered it so that it would not trigger infection in people. Then they further remodified it so that it carried the genetic blueprints for pieces of coronavirus. These would be carried into cells in the body, which would then start to make pieces of coronavirus to train people’s immune system to attack them. Armed with this technology, the Oxford scientists – later backed by the pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca – were then able to manufacture their vaccine and begin testing.

And it was at this time that the group encountered one of their worst moments. “Just a few days after we started vaccinating volunteers, a fake news website reported that the first person we had vaccinated had died,” said Pollard. “It was a lie, of course. Nevertheless I felt a huge responsibility, especially for all the people in our trial who we had already vaccinated. We had to move rapidly to reassure them – with a lot of help from the media who quickly debunked the story.”

The anti-vax movement is a concern, Pollard added. “I worry for those who are not vaccinated and also for the confusion and concern that these claims cause other people who may then not protect themselves. It is definitely an issue and we need to keep doing our best to explain the science and the safety of vaccines and reassure people.”

The Oxford team eventually collected data from their Phase 3 trials and presented them to UK regulators who, in December, gave final, full approval for their vaccine.

“It was hard work and it still is, but it’s hard work doing something that really matters,” said Gilbert. “We’ve got a huge number of people who have worked really, really hard on this for very many hours, day after day. It’s just relentless. But it helps that there are a lot of us doing it together.”

And just as researchers have made rapid changes in their work practices to produce vaccines, so has the public understanding of that work altered, said Pollard. “It is only when you go outside the office, you realise the whole world knows about clinical trials and safety reporting and regulators in a way that they never did before. It seems everyone is watching what we’re doing – which is not an experience I have ever had before. Indeed it’s always been quite difficult to persuade people to take an interest in my work!”

To date, Britain has inoculated more than 14 million people with the Oxford vaccine as well as the Pfizer version. It is an astonishing number, although Gilbert feels there are other aspects of the response that have been less impressive.

“Yes, it’s really heartening to see the NHS getting this vaccine out to so many people, but we haven’t fully used all the knowledge we have about coronaviruses. For example, we are still talking about the dangers of airborne viruses spreading in quarantine hotels. It has been known since the Mers outbreak in South Korea in 2015 that coronaviruses spread through the air.

“And yes, this particular virus came out of nowhere. But we have also known for a long time that a disease X, as WHO termed it, was going to appear at some point and start spreading. We had been warned. But again we weren’t ready.”

Gilbert also questioned the time it has taken to build the UK’s Vaccine Manufacturing Innovation Centre in Oxfordshire. Backed by £158m of government funding, it is intended to give Britain security over vaccine manufacture when the plant is completed at the end of the year.

“It is wonderful that we are getting the centre, but it won’t be ready until late 2021,” she said. “It would have been better if it had been up and running in 2020. It is going to help us in the future, but there wasn’t sufficient emphasis on getting it ready quickly.”

As to the kind of future that vaccines will give us, both Gilbert and Pollard are optimistic. “We might be able to live with Covid-19 as we do with other coronaviruses that infect us in childhood,” said Pollard. “I would be quite happy if I just get a cold with this virus in future – as long as we stop people dying from it. And the vaccines we have may be enough to achieve that. However, if the disease turns out to be more like flu, we may have to regularly update vaccines to maintain immunity in the population.

“That will be a huge problem if we have to do it for all age groups every year. However, I think there’s a reasonable chance that won’t be necessary and only the most vulnerable will need the vaccine every year, one that could be combined with flu vaccine in the future.”

Gilbert agreed that there was a good chance of life returning to some kind of normality in coming months. “Over the summer last year, I managed to go on a few country walks with friends. I really did enjoy that. Now I am looking forward to being able to do a lot more of that this summer.”

Covid timeline

9 January 2020

The first confirmed death from Covid-19 occurs in Wuhan. The first death outside China occurs on 1 February in the Philippines, and the first death outside Asia in France on 14 February.

11 January

Chinese virologist Zhang Yongzhen publishes the genome of the coronavirus responsible for the Covid-19 outbreak by putting his data on the internet. He had successfully sequenced the genome from swabs that had been taken from patients in Wuhan.

11 January

A team of scientists led by Sarah Gilbert - who had already created vaccines against other coronaviruses - begins work using Zhang’s data to create a Covid-19 vaccine.

30 January

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the director-general of the World Health Organization, declares the novel coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency of international concern, WHO’s highest level of alarm.

11 February

Gilbert and fellow Oxford scientist, paediatrician Andy Pollard, join forces to set up a large research team focused on developing a vaccine against Covid-19.

23 April

Trials of the vaccine on healthy human volunteers begin.

30 April

AstraZeneca and Oxford announce an agreement to develop and distribute a vaccine for Covid-19 infections.

23 November

Oxford and AstraZeneca announce results of their trials which indicate that their vaccine is highly effective in blocking Covid-19.

30 December

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine is approved for use in the UK by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

4 January, 2021

First doses of the vaccine are rolled out in the UK.

13 February

The UK reaches a total of more than 14 million people who have received at least one dose of a coronavirus vaccine - either the Pfizer or the Oxford vaccine - as part of the biggest inoculation programme the country has ever launched. The government pledge to have vaccinated 15 million by 15 February looks likely to be reached.